(2015) 390 KLW 725

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM

PRESENT: THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE DAMA SESHADRI NAIDU

WEDNESDAY, THE 10TH DAY OF DECEMBER 2014/19TH AGRAHAYANA, 1936

WP(C).No. 29261 of 2014 (G)

PETITIONERS

ASHOK KUMAR AND ORS.

BY ADVS.SRI.K.ABDUL JAWAD, SMT.VINEETHA V.KUMAR.

RESPONDENTS

1. OIL PALM INDIA LIMITED, REPRESENTED BY ITS MANAGING DIRECTOR, KOTTAYAM-686 001.

2. SENIOR MANAGER (HRD), OIL PALM INDIA LTD, YEROOR, PUNALUR TALUK, KOLLAM DISTRICT-691 305.

BY ADVS. SRI.M.GOPIKRISHNAN NAMBIAR, SRI.P.GOPINATH, SRI.P.BENNY THOMAS, SRI.K.JOHN MATHAI, SRI.JOSON MANAVALAN, SRI.KURYAN THOMAS.

JUDGMENT

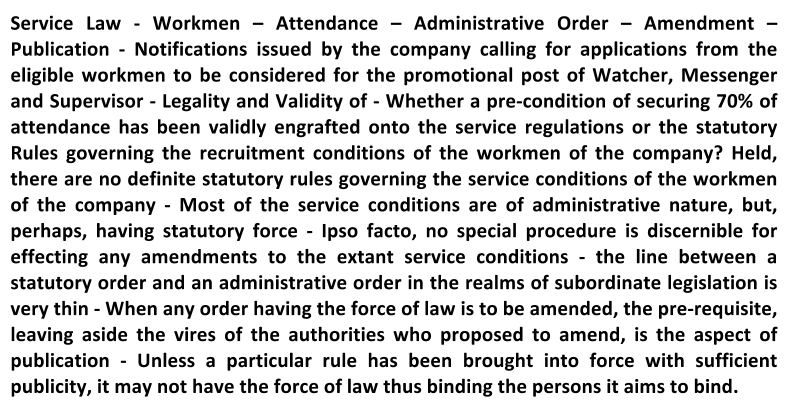

In this writ petition the issue that falls for consideration is the

legality and sustainability of imposing a pre-condition of securing 70% of attendance annually in a period of five years to be eligible for promotion from the feeder category of workmen in the respondent corporation.

2. The facts in brief are that the petitioners, ten in all, have been working as workmen in the first respondent company, which is a public sector undertaking, under the control of the Central Government. All of them have completed five years of service, the requisite minimum period to be eligible for the promotion to the posts, namely 'Watcher', 'Messenger' and 'Supervisor'.

3. Initially, the first respondent company issued Exhibit P4 notification dated 13.06.2013, and, later Exhibit P9 notification on 04.08.2014 calling for applications from the eligible candidates from the ranks of workmen to be appointed in the promotional post by transfer. The mode of selection being a written test and later interview, the petitioners were desirous of applying for the same. However, in the face of a pre-condition annexed to those notifications under reference that all workmen ought to have completed five years of service with 70% attendance annually, the petitioners approached this Court assailing Exhibits P4 and P9 notifications as being illegal and arbitrary and ultra vires, offending the constitutional canons.

4. In the above factual background, the learned counsel for the petitioners has submitted that the petitioners being workmen they discharge very arduous physical duties and accordingly they are prone to injuries. It is very difficult for any workmen to have 70% of attendance given the nature of duties they discharge. According to the learned counsel, until recently there was no such pre-condition of 70% annual attendance to be eligible for promotion as has been imposed now.

5. Elaborating on his submissions, the learned counsel would contend that as far as the workmen are concerned they are governed by the standing orders, whereas the promotional category, i.e. the staff category are governed by the recruitment and promotional rules. The learned counsel for the petitioners has drawn my attention to Clause 9.1 of the standing orders for workmen filed as Annexure A in the writ petition. The learned counsel has strenuously contended that Clause 9.1 alone governs the conditions of recruitment to the promotional category and that it does not contain any reference to the pre-condition of 70% attendance. In other words, any condition superimposed subsequently without amending the standing orders cannot have any impact on the recruitment process sought to be undertaken by the respondent company.

6. The learned counsel has also drawn my attention to Exhibit P6 which is an extract of the rules governing the service condition of the staff categories to which the petitioners have sought the promotion. It is the specific contention of the learned counsel that for all the three categories of Supervisor, Watcher and Messenger under Clauses 2.12, 2.13 and 2.14, the existing prescribed eligibility criteria are that the workmen should have completed five years of service and should be declared eligible in the written test and subsequent interview to be conducted for the promotional purpose.

7. The learned counsel has referred to Exhibit R1(a) and has submitted that though there is a resolution passed by the Board of Directors seeking to incorporate the pre-condition of 70% attendance, it was expressly made implementable only with the approval of the Government. In that regard, the learned counsel contends that so far the Government does not accord any approval to the proposed amendments. In other words, unless the rules have been amended in accordance with law established for the said purpose, Exhibit R1(a) cannot be treated as part and parcel of the Rules thereby imposing a pre-condition. He has also further contended that the very resolution has never stated that the Rules are being amended incorporating Clause 26 of Exhibit R1(a).

8. Nextly, referring to Exhibit R1(c), which is the resolution No.2502, the learned counsel has contended that it has no reference to Exhibit R1(a) and ipso facto the Board's decision to implement the resolutions having no financial commitment without reference to the Government does not apply to Exhibit R1(a) resolution. He has strenuously contended that amendment is sine qua non and in its absence any number of resolutions would remain only mere administrative instructions having no force. He has also contended that both Exhibits R1(a) and R1(c), the resolutions of the Board of the first respondent company, suffer from the vice of ambiguity.

9. The learned counsel has referred to Exhibit R1(b) which is a notice dated 08.03.2010 and has contended that the respondent company has its branches across the state at various places and it is not clear from Exhibit R1(b) that the notice has been given sufficient publicity concerning the proposed amendments by disseminating the information in all the places where the respondent company has its activities and offices. He has also pointed out that Exhibit R1(b) in fact precedes Exhibit R1(c). To that extent, the learned counsel has even doubted the veracity of Exhibit R1 (b).

10. Summing up his submissions the learned counsel has submitted that the only excuse that has come forward from the respondent company is that before giving effect to the resolution, especially before issuing Exhibits P4 and P9 notifications, even the workmen union has been taken into confidence. He repels the said contention by submitting that the petitioners belong to different unions and in fact different workmen are represented by different unions. Taking into account that the alleged consent of one union cannot displace the statutory requirement on the part of the respondent company to amend the Rules, especially by giving wide publicity to them, the learned counsel has submitted that the precondition of 70 per cent cannot be sustained. Thus, contends the learned counsel that the writ petition is required to be allowed thereby providing an opportunity to the petitioners to be considered for the promotional posts.

11. Per contra, the learned Standing Counsel for the respondent company has submitted that prior to 22.04.2005 there was a condition of 15 years as the minimum service required as a pre-condition to be eligible to the promotional posts from the feeder category of workmen. On 22.04.2005, the Rules were amended bringing down the period of experience from 15 years to 5 years. The learned Standing Counsel has strenuously contended that whatever the procedure that had been adopted in 2005 when the Rules were amended incorporating five years as the minimum service has been followed in the present instance, too, when the respondent company desired to introduce the additional requirement of 70% annual attendance. According to her, having taken advantage of the amendment of 2005, the petitioners are estopped from questioning the subsequent amendment merely on the premise that that has not been to their liking.

12. Underlining the purpose behind the incorporation of pre-condition of minimum attendance, the learned Standing Counsel would contend that there are three categories of posts in the first respondent organization; namely, Officers, Staff, and Workmen. Most of the time the workmen do not work continuously for five years, but work only intermittently. In the end somehow they ensure that they have completed five years so that they could claim promotion. Only to plug the said loophole and to ensure that the regular workmen alone are given the opportunity of promotion, the first respondent company has thought it fit to introduce the said condition.

13. The learned Standing Counsel has submitted that Exhibit R1(a) resolution reserving, inter alia, to impose the additional condition of 70% minimum attendance was passed on 06.12.2009, whereas the notice publishing the said amendment was issued in Exhibit R1(b) on 08.03.2010. Subsequently Exhibits P4 and P9 notifications were issued in 2013 and 2014 respectively. According to the learned Standing Counsel, the respondent company provided sufficient time after Exhibit R1(b) notification so that all the workmen could come to know about the changed eligibility criterion before Exhibits P4 and P9 notifications were issued.

14. The learned Standing Counsel has also drawn my attention to Article 29 of Memorandum of Association and Articles of Association of the respondent company to underline the powers of the Board, which according to the learned counsel, has plenary powers concerning the amendment, especially with regard to the modalities of recruitment.

15. Finally the learned Standing Counsel has submitted that the writ suffers from laches inasmuch as, though Exhibit P4 notification was issued way back in 2013, i.e., more than one year ago, the petitioners did not choose to challenge it. According to her, only just a couple of days prior to the last date under Exhibit P9 notification, dated 04.08.2014, did the petitioners rush to the court.

16. Summing up her submissions, the learned Standing Counsel has submitted that only two issues fall for consideration in the present writ petition; namely, whether the Board has the power to amend the Rules, and whether the petitioners have approached this Court on time. In elaboration of her submissions the learned Standing Counsel would contend that insofar as the first aspect is concerned, it is indisputable that the respondent Board has plenary powers; and insofar as the second issue is concerned, the writ suffers from laches. Accordingly, the learned Standing Counsel urges this Court to dismiss the writ petition as devoid of merit.

17. In reply, the learned counsel for the petitioners has contended that some of the petitioners in fact responded only to Exhibit P9 notification which was issued on 04.08.2014 and as such it cannot be said that there is any inordinate delay on the part of petitioners in approaching this Court. He has further contended that when it comes to an issue of career prospects or advancement, this Court may not throw out cases on mere technicalities.

18. Heard the learned counsel for the petitioners and the learned Standing Counsel for the respondent company, apart from perusing the record.

19. Indeed, the sole issue that falls for consideration is the legality and validity of Exhibits P4 and P9 notifications issued by the respondent company calling for applications from the eligible workmen to be considered for the promotional post of Watcher, Messenger and Supervisor.

In other words,

whether a pre-condition of securing 70% of attendance has been validly engrafted onto the service regulations or the statutory Rules governing the recruitment conditions of the workmen of the respondent company?

20. At the outset it is to be observed that the respondent, though an instrumentality of State in terms of both Articles 12 and 226 of the Constitution of India, is, however, is not a statutory body under any special enactment. It has, in fact, been brought into existence as an entity under the Companies Act 1956. Had it been an entity brought under a special enactment, there could have been its own statutory parameters concerning the subordinate legislation and also the manner of effecting amendments to the said legislation. Thus, in the present instance, there are no definite statutory rules governing the service conditions of the workmen of the respondent company. Most of the service conditions are of administrative nature, but, perhaps, having statutory force. Ipso facto, no special procedure is discernible for effecting any amendments to the extant service conditions.

21. It is not in dispute that the line between a statutory order and an administrative order in the realms of subordinate legislation is very thin. When any order having the force of law is to be amended, the pre-requisite, leaving aside the vires of the authorities who proposed to amend, is the aspect of publication. Unless a particular rule has been brought into force with sufficient publicity, it may not have the force of law thus binding the persons it aims to bind. In the present instance, it is not in dispute that in terms of Article 29 of the Memorandum of Association and Articles of Association of the respondent company, the Board itself has plenary powers to effect amendments to the service conditions including the Rules that are falling for consideration presently.

22. Through Exhibit R1(a) a resolution was passed on 06.12.2009. There is no gainsaying the fact that at the end of the resolution there was a specific recording that the decision taken by the Board of Directors may be implemented with the approval of the Government. On this observation the learned counsel for the petitioners has laid heavy stress. According to him, it squarely binds the authorities and they cannot wriggle themselves out of their own commitment to have the prior approval of the Government before they could enforce any of the measures they have taken through Exhibit R1(a) resolution. Appealing as the submission may be, the fact however remains that unless any particular law or any regulation having the force of law mandates that the Board cannot implement its resolutions without the prior approval of the Government, it cannot come in the way as a matter of estoppel, just because the Board has initially resolved to do so, for there can be no estoppel against the statute. Further, the very resolution has been couched in directory terms with the expression 'may'. If we proceed further, it can be seen that in Exhibit R1(c), it has been further resolved soon thereafter that the respondent company is required to obtain the prior permission or sanction of the Government only concerning the issues that involve financial commitments, but not with regard to other issues.

23. It is indisputable that the amendment of the service conditions of the workforce of the respondent company does not involve any extra financial commitment on the part of the respondent company.

24. Now, once it is conceded that the respondent company, through its Board of Directors, has the power to amend the Rules, the next question that falls for consideration is whether the Rules have been amended in the manner known to law, after following the due process and after proper publication.

25. If we peruse Exhibit R1(b) dated 08.03.2010, it is evident that the resolution concerning imposing the condition of 70% attendance each year in addition to the five year service was notified much prior to Exhibits P4 and P9. Indeed the learned counsel for the petitioners has strenuously contended that the respondent company has different unions across the State and it is not discernible from Exhibit R1(b) that there had been any wide notification concerning the issue of 70% attendance. As has been observed earlier, neither the Memorandum and Articles of Association, nor the very Rules which govern the service conditions of the staff cadre, prescribed any particular mode of publication of the Rules. In that sense as a matter of common law principle all that is required is to have wide publicity. In fact, wide publicity is a word of relative connotation.

26. In the absence of any prescribed mode of publication, the underlying theme could be dissemination of information so that the affected persons thereby could come to know of the changes in advance, lest they should be taken by surprise.

27. In this respect, the observations of the learned authors MP Jain & SN Jain in their scholarly treatise Principles of Administrative Law, (page160, Vol.1, 7th Edn.) are instructive:

This point was settled by the Supreme Court in

In the instant case, the law in question made by the Executive had remained buried in the Government archives without ever seeing the light of the day. There was no law at the time requiring publication when the law in question was made. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court held the law to be invalid. The Court emphasized the promulgation or publication of some reasonable sort is essential to bring a law into force as it would be against natural justice to punish people under a law of which they had no knowledge and of which they could not, even with the exercise of reasonable diligence, have acquired any knowledge. Thus, what the court held in the instant case was that promulgation or publication of some reasonable sort was essential to bring the law into being, to make it legally effective, but the Court left it vague as to what channels of publication were to be adopted.

In

publication of delegated legislation was required by the Act and finding was that there was publication as required by the Act, still the court made general observation in line with Harlas's case that publication in some form is necessary for making the delegated legislation effective. It was also observed that if the Act or the delegated legislation itself prescribes the mode of publication, that mode of publication should be adopted but if no mode of publication is prescribed the publication should be in the Official Gazette or in some other reasonable form."