(2015) 394 KLW 618

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM

PRESENT: THE HONOURABLE THE AG.CHIEF JUSTICE MR.ASHOK BHUSHAN THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE T.R.RAMACHANDRAN NAIR THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE K.SURENDRA MOHAN THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.V.RAMAKRISHNA PILLAI & THE HONOURABLE SMT. JUSTICE P.V.ASHA

FRIDAY,THE 20TH DAY OF FEBRUARY 2015/1ST PHALGUNA, 1936

WP(C).No. 31599 of 2009 (T), W.P(C).No.7910 of 2012, W.P(C).No.7032 of 2013, W.P(C).No.7816 of 2013, W.P(C).No.15379 of 2013 W.A.No.149 of 2010 & W.A.No. 150 of 2010

PETITIONER(S)

K.L. FRANCIS

BY ADV. SRI.N.UNNIKRISHNAN

RESPONDENT(S)

1. THE KERALA STATE ROAD TRANSPORT CORPORATION, TRANSPORT BHAVAN, FORT, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, REP.BY ITS MANAGING DIRECTOR.

2. THE ASSISTANT TRANSPORT OFFICER, KSRTC, ADOOR.

BY ADV. SRI.M.GOPIKRISHNAN NAMBIAR, S.C

JUDGMENT

Ashok Bhushan, Ag.CJ.

This Larger Bench has been constituted on a reference made by a three Judge Bench by referring order dated 15.2.2014, in which the correctness of a Full Bench decision in District Transport Officer v. Kunchan (2009 (3) KLT 954(FB)) has been doubted. By the said reference order, these five Writ Petitions and two Writ Appeals have been referred to Larger Bench.

2. W.P(C).No.31599 of 2009 is being treated as the leading Writ Petition. It is sufficient to refer to the facts and pleadings in the leading Writ Petition for answering the reference and deciding all these cases. The brief facts giving rise to W.P(C).No.31599 of 2009 are: The petitioner joined the service of the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (hereinafter referred to as 'KSRTC') as empannelled Driver on daily wage at Adoor Depot in February, 1995. He continued as such till his selection by the Kerala Public Service Commission (hereinafter referred to as 'PSC') and consequent appointment as reserve Driver on the basis of advice memo dated 22.6.2000. The petitioner was appointed as reserve Driver in pay scale of Rs.3,000-6,685/-with effect from 19.7.2000. He became Driver Grade-II with effect from 28.5.2001. He continued in service till 31.12.2007, when he attained the age of superannuation. His service, after regular appointment, was only 7 years 5 months and 13 days. According to the Kerala Service Rules, Part III, minimum qualifying service for pension is ten years. The KSRTC has adopted the Kerala Service Rules, Part III for its employees. A memorandum of settlement was entered between the KSRTC through its Chairman and Managing Director and the Kerala State Road Transport Employees Association dated 13.4.1999. The said agreement was also approved by the Government of Kerala by G.O(MS) No.9/99-TRAN dated 9.4.1999. The memorandum of settlement contained various clauses covering scales of pay, dearness allowance, house rent allowance, medical reimbursement, special allowance, travelling allowance and several other subjects including pension. Annexure-IV to the settlement contained different categories of posts divided in 11 sections totalling 161. Thus, the settlement covered 161 categories of posts (learned counsel for the KSRTC placed before the Court a copy of the agreement dated 13.4.1999 for perusal of the Court). As noted above, the agreement contained clause XXIII-Pension. For the purpose of pension, daily wage period of Conductors, drivers and mechanical staff before their regular appointment was to count subject to condition as mentioned in clause XXIII-3.

3. The petitioner, after retirement, has submitted a representation to the Chairman and Managing Director of the KSRTC requesting to add provisional service rendered by him before his regular service. In the representation he placed reliance on a Division Bench judgment of this Court in

Idicula Abraham v. K.S.R.T.C (2005(2) KLJ 602)

It was stated that the judgment of the Idicula Abraham's case (supra) has been implemented, hence he is also entitled to count his provisional service for pension and pensionary benefits. The petitioner filed W.P(C).No.26795 of 2008 seeking a declaration that he is entitled to count his qualifying service for pension. This Court by judgment dated 16.7.2005 disposed of the Writ Petition directing to take decision on the representation submitted by the petitioner for pensionary benefits. In pursuance of the above judgment, an order dated 14.10.2009 was issued by the KSRTC rejecting the claim of the petitioner to count his daily wage service prior to his regular appointment. It was stated that though in the wage revision settlement 1997 it was provided that daily wage period shall be taken into account for pension, the same is applicable to those who got appointment through the Employment Exchange. Challenging the decision of the KSRTC, the Writ Petition was filed by the petitioner praying for the following reliefs:

"i) call for the records leading issuance of Exhibit- P11;

ii) declare that the Ext.P11 is unsustainable in the eyes of law;

iii) issue a writ of certiorari or appropriate writ or order quashing Exhibit-P11; iv) declare that petitioner is entitled to count the provisional service rendered as evidenced in Ext.P1 followed by regular appointment for the purpose of regular pension and pensionary benefits; v) issue a writ of mandamus or appropriate writ or order or direction to issue necessary orders to the respondents to count the provisional service rendered by the petitioner as Driver as evidenced in Exhibit-P1 prior to regular appointment as per Ext.P2 to P4, for the pension and other service benefits and to release service benefits accrued thereon to him within a reasonable time; AND

vi) Issue such other or further appropriate writ or order or direction as this Hon'ble Court may deem fit, just and necessary in the circumstances of the case including the cost of this writ petition (Civil)."

4. It is useful to note that in all the Writ Petitions, including the Writ Petitions giving rise to W.A.Nos.149 and 150 of 2010, the petitioners have claimed addition of their provisional/daily wage period for the purpose of pension, whereas in two Writ Petitions, i.e., W.P(C).Nos.7032 and 7816 of 2013 the petitioners have claimed that their provisional period be added for the purpose of seniority. It is necessary to note the facts of above two Writ Petitions and the reliefs claimed.

5. W.P(C).No.7032 of 2013 has been filed by two petitioners, who claimed to be appointed as provisional drivers on 17.3.1997 and 21.4.1997 respectively. The petitioners continued as provisional drivers till 6.7.2000 and 21.7.2000 respectively, when they were selected and appointed as reserve drivers through the Kerala Public Service Commission. The following reliefs have been prayed in the Writ Petition:

"i. To issue a writ of mandamus, any other appropriate writ, order or direction commanding the resopndents to confer seniority to the petitioners in respect of their provisional service to be merged with their present seniority for the period 17.03.1997 to 19.07.2000 in respect of the 1st petitioner and 21.04.1997 to 21.07.2000 in respect of the 2nd petitioner forthwith.

ii. To declare that the petitioners are entitled to be conferred seniority in respect of their provisional service to be merged with their present seniority for the period 17.03.1997 to 19.07.2000 in respect of the 1st petitioner and 21.04.1997 to 21.07.2000 in respect of the 2nd petitioner forthwith."

6. In W.P(C).No.7816 of 2013 there are five petitioners. All the five petitioners have initially joined as provisional drivers in the year 1996 and 1998 (only fifth petitioner). All the petitioners were subsequently appointed as reserve drivers through the Kerala Public Service Commission and joined in the regular service in the year 2000. The petitioners claim that their provisional service period be merged with their regular period for seniority and other purposes. The following prayers have been made in the Writ Petition:

"i. To issue a writ of mandamus, any other appropriate writ, order or direction commanding the respondents to confer seniority to the petitioners in respect of their provisional service to be merged with their present seniority for their respective period of their provisional service forthwith.

iii. To declare that the petitioners are entitled to be conferred seniority in respect of their provisional service to be merged with their present seniority for their respective period of provisional service."

7. When the Writ Petitions came up for hearing, the learned Single Judge considered a Full Bench judgment of this Court in Kunchan's case (supra) relied on by learned counsel for the KSRTC. It was contended that temporary services rendered by a candidate not advised by the PSC cannot be taken into consideration for the purpose of computation of pension. Learned counsel for the petitioner submitted that the settlement dated 13.4.1999 is binding on the KSRTC, wherein daily wage service is eligible for pensionary benefits subject to fulfilment of certain conditions. The petitioner placed reliance on the judgment of the Apex Court in

National Textile Corporation (APKKM) Ltd. v. Sree Yellamma Cotton, Woollen and Silk Mills Staff Association and others [(2001)2 SCC 448]

The learned Single Judge by his order dated 20.6.2012 opined that Full Bench needs reconsideration. The matter was placed before a Division Bench, who, by order dated 3.7.2012, directed the matter to be placed for consideration of a Full Bench. The said order of the Division Bench is to the following effect:

"The question raised in the order of reference made by the learned single judge, in its totality, is as to whether the decision rendered by the Full Bench of this Court in

requires re- consideration in the light of the judgments of the Supreme Court in

and

It is also pointed out that the judgment of the Division Bench in W.A. 2243/06 has not been appreciated by the Full Bench. Incidentally, it is also pointed out that though Idicula Abraham v. K.S.R.T.C. [2005 (2) KLJ 602] stands overruled in Kunchan (supra), the SLP against the judgment in Idicula (supra) was dismissed by the Apex Court and that fact was not brought to the notice of the Full Bench. Though we do not prima facie see that a case of merger of judgments could result out of the dismissal of the SLP, we are inclined to think that judgment of the Division Bench in W.A.2243/06, which deals with the effect of bipartite settlement, has escaped the notice of the Full bench. That apart, the latter decision of the Apex Court also appears to have a bearing on the issue whether it is necessary to refuse pensionary benefits to those who have entered service otherwise than through PSC, even if they have discharged duties and responsibilities at par with employees/workmen recruited through PSC. We, accordingly, refer these cases for the consideration of the Full Bench. The office will place these files before the Hon'ble the Chief Justice for further orders."

Consequently, the matter was placed before a three Judge Bench. The Full Bench, after noticing the contentions of the rival parties and referring to the Full Bench judgment in Kunchan's case (supra), referred the matter to be considered by a Larger Bench by making the following observations:

"5. Ext.P5 produced in W.P(C) No.31599/2009 is the copy of the memorandum of settlement wherein, clause XXIII refers to "pension" and sub-clause 3 is the one which comes up for interpretation. We extract the same hereunder :

"3. Daily wages period of conductors, Drivers and Mechanical staff before their regular appointment in full, will count for pension there should be at lease ten days duty in a month. If there is no duty in a month, that month will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below then or 50% of the total daily wage period of excluding the months having no duty whichever is beneficial to the employees."

The Full Bench in Kunchan's case (2009 (3) KLT 954- FB), considered the matter in the case of two sets of employees. The first one is in the case of a person included in the rank list published by the public Service Commission for appointment as Driver, but he was appointed as Driver on daily wages initially and was later absorbed in the regular service. The Corporation declined to count the service rendered by him as daily wages employee in the same post as part of the qualifying service for pension. While answering the said contention, it was held that the entire service is eligible to be treated as qualifying service for the purpose of pension. While considering issue No.2, the Full Bench considered the legality of the dictum laid down in Idicula's case (2005 (2) KLJ 602). Therein, the writ petitioner was a daily rated Reserve Driver who was advised by the Employment Exchange prior to his entry in regular service as a Reserve Driver on advice by the Public Service Commission. After relying upon the decision of the Apex court in

State of Karnataka v. Umadevi [(2006) 4 SCC 1)

it was held that such casual service cannot be treated as regular service to be reckoned for all intents and purposes Finally, in paragraph 27, while considering the terms of settlement, the Full Bench observed that

"where a term of settlement, to which an instrumentality of a State is a party, provides for treating casual service also as part of regular service for all intents and purpose, then it will only be appropriate to treat only such casual service, rendered by a person, who has already been advised by the Commission for regular appointment against the post in question as part of regular service. Any other kind of casual service would only be casual service that cannot be considered as synonymous with regular service."

6. The question, therefore, will be whether the settlement will be binding on the employer, in the light of section 18(3) (d) of the Industrial Disputes Act. Shri. N. Unnikrishnan submitted that the settlement has not been terminated in accordance with law, as provided in Section 19 of the Industrial Disputes Act. Therefore, according to him, in such cases the Corporation cannot be allowed to go back on the settlement. We are also of the view that this specific question will have to be considered.

7. Since the correctness of the Full bench in Kunchan's Case (2009 (3) KLT 954-FB) is canvassed before us, the matter will have to be heard by a Larger Bench. The effect of the decision of the Apex Court referred to already and the view taken by the Division Benches in Idicula Abraham's case (2005 (2) KLJ 602) as well as in Mohanan Nair's case (W.A. No.2243/2006) being rendered on the interpretation of the terms of a settlement which have not been considered in detail by the Full Bench in Kunchan's case (2009 (3) KLT 954-FB), it is only appropriate that the matter is heard by a Larger Bench."

7. We have heard Sri.N.Unnikrishnan, Sri.Justine K.P (Karipat), Sri.K.P.Rajeevan, learned counsel appearing for the writ petitioners and Sri.P.Gopinath, learned Standing Counsel for the KSRTC.

8. Learned counsel for the petitioner submitted that the writ petitioner was entitled to reckon the period of daily wages prior to his regular appointment on the basis of settlement dated 30.4.1999 entered by the KSRTC, wherein daily wage period of Drivers and Conductors is eligible for pensionary benefits subject to conditions mentioned therein. It is submitted that the KSRTC cannot now contend that daily wage period of only one category of Drivers, i.e., those who have been appointed on daily wages after having been advised by the PSC is eligible for pensionary benefits. It is submitted that the Full Bench judgment in Kunchan's case (supra) does not lay down the correct law by splitting the daily wage period of the Drivers and Conductors in two categories. The settlement does not envisage any such splitting of daily wage period of Drivers and Conductors and the KSRTC cannot deny its liability to reckon the daily wage period for pensionary benefits. The settlement is binding between the parties, since it has never been questioned as per the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. It is submitted that the settlement was also approved by the State Government by Government Order dated 9.4.1999 and the State Government is entitled to issue directions regarding any specified service for the purposes of pension. It is submitted that the Division Bench judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) laid down the correct law, against which the KSRTC filed a Special Leave Petition and the Supreme Court had dismissed the Special Leave Petition. It is submitted that the judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) was also implemented by the KSRTC and many Drivers/Conductors similarly situated have already been given the benefit of daily wage period for the purpose of pension. The Full Bench in Kunchan's case (supra) travelled beyond the issue, which was involved in the said case. There is no valid classification in two types of daily wage services of Drivers and Conductors as has been carved out in Kunchan's case (supra). The Full Bench virtually has struck down the settlement, which it could not have done. The judgment in

Secretary, State of Karnataka & others v. Umadevi(3) and others [(2006) 4 SCC 1]

has no application in the facts of the present case and the Full Bench has wrongly placed reliance on the said judgment.

9. Sri.P.Gopinath, learned Standing Counsel for the KSRTC, refuting the submissions of learned counsel for the petitioners, submitted that it is only the regularly recruited employees who are entitled to reckon their period for pension. He submits that the Full Bench judgment in Kunchan's case (supra) laid down the correct law that the daily wage period can be reckoned for the purpose of pension only when the said daily wage appointment has been made after recommendation by the PSC. It is submitted that appointment on the basis of rank list of the PSC takes years, hence in between when provisional appointment is given to an employee, the said period can only be reckoned for the purpose of pension. The petitioners were empanelled on daily wage and it was only after working for few years that they could be selected and recommended by PSC, hence their period prior to recommendation by PSC cannot be added for purpose of pension. Referring to clause XXIII-3 of the settlement dated 13.4.1999 it has been submitted that the said clause is to be interpreted in accordance with law declared by the Supreme Court in Umadevi's case (supra). It is submitted that the Supreme Court in Umadevi's case (supra) has laid down that daily wagers had no right to claim regularisation, nor the daily wage period can be basis for claiming regular appointment. He submits that daily wage period cannot be reckoned for the purpose of pension. It is submitted that clause XXIII-3 of the settlement has to be interpreted in the manner that it contemplated the daily wage period only after recommendation by the PSC. He submits that all appointments in the KSRTC are made on the recommendation of the PSC, hence the Full Bench in Kunchan's case (supra) has rightly construed the above clause XXIII-3. He submits that the KSRTC has filed W.A.Nos.149 an 150 of 2010 challenging the judgment of the learned Single Judge by which judgment the learned Single Judge directed for adding the daily wage period following the judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra).

10. Learned counsel for the parties have relied on various judgments of this Court and the Apex Court, which shall be referred to while considering the submissions in detail.

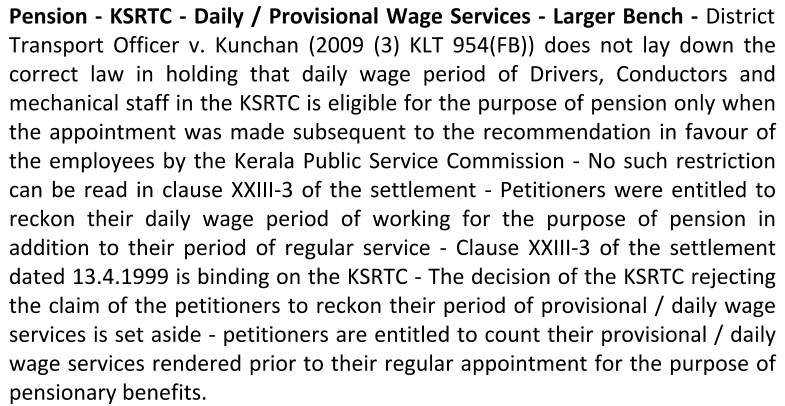

11. From the submissions made by learned counsel for the parties and the pleadings on record, the following are the issues, which have come up for consideration before the Larger Bench:

I. Whether the Full Bench of this Court in District Transport Officer v. Kunchan (2009 (3) KLT 954(FB)) lays down the correct law in so far as it holds that daily wage period of Drivers, Conductors and mechanical staff in the KSRTC is eligible for the purpose of pension only when the Daily wage appointment was made subsequent to recommendation in favour of the employees by the Kerala Public Service Commission and working on daily wages in any other capacity cannot be taken into consideration for the purpose of pension?

II. Whether the petitioners in the Writ Petitions before us were entitled to reckon their Daily wage period of working as Driver in the KSRTC for the purpose of pension?

III. Whether clause XXIII-3-Pension of the settlement dated 13.4.1999 is binding on the KSRTC to reckon the daily wage period of Drivers, Conductors and mechanical staff for the purpose of pension?

IV. Whether the judgment of the Supreme Court in Secretary, State of Karnataka & others v. Umadevi(3) and others [(2006) 4 SCC 1] is applicable while interpreting clause XXIII-3 of the settlement dated 13.4.1999

12. All the above issues being inter-related are being taken together.

13. Before we enter into the issues noted above, it is relevant to refer to statutory provisions governing the pension in the State of Kerala. Learned Standing Counsel for the KSRTC has submitted that the KSRTC has adopted the Kerala Service Rules Part III and is following the same for determining the entitlement of pension of its employees. The above position has already been accepted in various judgments of this Court, including the Division Bench judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra). The Kerala Service Rules Part III deals with pension. Rule 4 enumerates certain cases in which claim of pension is not admitted. Rule 4 of the Kerala Service Rules Part III is as follows:

"4. In the following cases, no claim to pension is admitted:-

(a) When an employee is appointed for limited time only, or for specific duty, on the completion of which he is to be discharged.

(b) When a person's whole time is not retained for the public service, but he is merely paid for work done for the State.

(c) When a person is employed temporarily on monthly wages without specified limit of time or duty.

(d) When an employee holds some other pensionable office, he earns no pension in respect of an office of the kind mentioned in clause (b) or in respect of duties paid for by local allowance."

14. Chapter II of Part III of the Kerala Service Rules deals with qualifying service. Rules 10 and 11 are as follows:

"10. The service of an employee does not qualify for pension unless he is appointed, his duties regulated and paid by the Government or under conditions determined by the Government.

11. Notwithstanding the provisions of Rule 10, the Government may, (1) declare that any specified kind of service rendered shall qualify for pension; and (2) in individual cases, and subject to such conditions as they may think fit to impose in each case, allow service rendered by an employee to count for pension."

15. According to Rule 57, minimum service for pension is ten years. Rules 10 and 11 read together clearly provide that the Government may declare that any specified kind of service rendered shall qualify for pension. A Division Bench of this Court in

Kunju Mohammed M.A v. KSRTC (ILR 2009(3) Kerala 451)

has laid down that when the KSRTC adopts the said Rule, it should be read as enabling the KSRTC to declare other services also as qualifying service. A perusal of the scheme of the Kerala Service Rules Part III, as noted above, it is clear that ordinarily a daily wage employment is not eligible for the purpose of pension. Daily wage period can be added only when there is a declaration of the Government/KSRTC with regard to any specified kind of service as per Rule 11.

16. Present is a case where the petitioners are claiming their entitlement to reckon their daily wage period on the strength of the settlement dated 13.4.1999 entered into between the KSRTC and the Employees' Association. The settlement dated 13.4.1999 is also not denied or questioned by the KSRTC. Clause XXIII relates to pension. It is useful to extract clause XXIII of the settlement, which is to the following effect:

"XXIII Pension

1. Pension will be paid as per the provisions of Kerala Service Rules followed by the Government from time to time.

2. Service under State Government prior to joining the Corporation will qualify for pension provided the break between Government service and K.S.R.T.C service shall not exceed three months.

3. Daily wages period of Conductors, Drivers and Mechanicals Staff before their regular appointment in full, will count for pension provided there should be at least ten days duty in a month. If there is no duty in a month, that month will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below 10 or 50% of the total daily wage period excluding the months having no duty whichever is beneficial to the employee.

4. Pre-appointment training period of Mechanical Staff including Assistant Depot Engineers will be treated as qualifying service for pension."

17. A perusal of clause XXIII-3 indicates that the settlement contemplates that daily wage period of Conductors, Drivers and Mechanical staff before their regular appointment in full, will count for pension, provided there should be at least ten days duty in a month. If there is no duty in a month, that month will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below 10 or 50% of the total daily wage period excluding the months having no duty whichever is beneficial to the employee.

18. The above settlement is referable to Section 18 (1) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. According to Section 18(1), the settlement arrived at by agreement between the employer and the workmen shall be binding on the parties to the agreement. Section 18(1) is quoted as below:

"18. Persons on whom settlements and awards are binding.- (1) A settlement arrived at by agreement between the employer and workman otherwise than in the course of conciliation proceeding shall be binding on the parties to the agreement."

19. Section 19 of the I.D. Act deals with the period of operation of settlement and awards. Section 19(1) and (2) is quoted as below:

"19. Period of operation of settements and awards. - (1) A settlement shall come into operation on such date as is agreed upon by the parties to the dispute, and if no date is agreed upon, on the date on which the memorandum of the settlement is signed by the parties to the dispute. (2) Such settlement shall be binding for such period as is agreed upon by the parties, and if no such period is agreed upon, for a period of six months from the date on which the memorandum of settlement is signed by the parties to the dispute, and shall continue to be binding on the parties after the expiry of the period aforesaid, until the expiry of two months from the date on which a notice in writing of an intention to terminate the settlement is given by one of the parties to the other party or parties to the settlement."

20. The Apex Court had occasion to consider Sections 18 and 19 of the Industrial Disputes Act in context of settlement in National Textile Corporation (APKKM) Ltd (supra). Explaining the legal position during the subsistence of the settlement, following was laid down by the Apex Court in paragraph 2 of the judgment:

"2. ......Undoubtedly, the legal position is that during the subsistence of a settlement it is not open to any of the parties to raise a dispute. A settlement once entered into between the parties shall be operative until the same is terminated as provided in Section 19 of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (hereinafter referred to as "the Act"). The object of such a provision is to ensure that once a settlement is entered into then industrial peace prevails according cordialities between the parties during the period agreed upon. The same position should continue by extension of the settlement by operation of law. There is an option given to either party to terminate the settlement and such a course having not been adopted in the present case the dispute could not have been raised by the parties......"

21. Again the Apex Court in

I.T.C. Ltd. Workers' Welfare Association v. Management of I.T.C. Ltd. and others (2002(1) LLJ 294)

had occasion to consider the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. The Apex Court was considering the settlement arrived at in the course of conciliation proceedings. As the settlement was arrived at between the employer and workmen, the settlement is binding on the parties. Following was laid down by the Apex Court in paragraphs 13 and 21 of the judgment:

"13. In answering the reference the industrial adjudicator has to keep in the forefront of his mind the settlement reached under section 12(3) of the Industrial Disputes Act. Once it is found that the terms of the settlement operate in respect of the dispute raised before it, it is not open to the Industrial Tribunal to ignore the settlement or even belittle its effect by applying its mind independent of the settlement unless the settlement is found to be contrary to the mandatory provisions of the Act or unless it is found that there is non-conformance to the norms by which the settlement could be subjected to limited judicial scrutiny. This is in fact the approach of the Tribunal in the instant case. The High Court which examined the issue from a different angle as well as, in our view, justified in affirming the award of the Tribunal.

xx xx xx

21. What follows from a conspectus of these decisions is that a settlement which is a product of collective bargaining is entitled to due weight and consideration, more so when a settlement is arrived at in the course of conciliation proceeding. The settlement can only be ignored in exceptional circumstances viz., if it is demonstrably unjust, unfair or the result of mala fides such as corrupt motives on the part of those who were instrumental in effecting the settlement. That apart, the settlement has to be judged as a whole, taking an overall view. The various terms and clauses of settlement cannot be examined in piecemeal and in vacuum."

22. The binding nature of settlement entered between the parties containing Clause XXIII as quoted above has never been questioned by the K.S.R.T.C, nor before us. Learned counsel for the KSRTC has not made any submission to impeach the binding effect of the settlement. What has been canvassed before us is that clause XXIII-3 of the settlement has to be interpreted in a manner as has been interpreted by the Full Bench of this Court in Kunchan's case (supra).

23. Before we refer to the above submissions of learned counsel for the KSRTC, it is necessary to refer to two Division Bench judgments of this court rendered on the subject under consideration. Idicula Abraham's case (supra) was a judgment delivered by a Division Bench of this court in a Writ Appeal filed by the petitioners who were working as Drivers in the KSRTC. The facts of the above case were that the petitioners were employed as daily-rated reserve in the KSRTC from 1981 onwards. They were continuously working on daily wage basis till they were permanently appointed through the PSC in the year 1989. One of the petitioners in that case was appointed on regular basis as Driver on the advice of PSC on 29.5.1989 and he retired from service on 30.4.2002. The facts of the case has been noted in paragraph 1 of the judgment, which is to the following effect:

"1. Petitioners were employed as daily-rated reserved in the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation from 1981 onwards. They were continuously doing the work on daily wage basis till they were permanently appointed through the Public Service Commission. We refer to the date of appointment mentioned in O.P. No.32947 of 2002 (W.A. No.1636 of 2003). Petitioner in that case who was advised by the Employment Exchange was appointed as Driver on provisional basis on 29.06.1981. Petitioner was appointed on regular basis as Driver on the advice of the Kerala Public Service Commission on 29.05.1989. Therefore, on 03.06.1989 provisional appointment was terminated and he joined duty as regular Driver on 05.06.1989. He retired from service on 30.04.2002. He wanted his daily rated provisional service to be counted for pensionary benefits. That was disallowed and hence the writ petition was filed."

Before the Division Bench the petitioner has laid his claim on the basis of clause XXIII of the settlement, which was quoted by the Division Bench. The KSRTC rejected the claim of the petitioner, hence the Writ Petition was filed seeking a direction to add the daily wage period for the purpose of pension. The learned Single Judge took the view that workers, who are referred to in the settlement, are daily-rated workers, who were appointed after they were advised by the PSC. The Division Bench refused to interpret clause XXIII-3 in the above manner and held that there are no such restrictions in the settlement or Government order. The Court held that clause XXIII shall be applicable for reckoning the period of daily wage employment and cannot be restricted only to the daily wage employment after recommendation by the PSC. The Writ Appeal was allowed. It is useful to quote paragraph 4 of the judgment, which contains the reasons and discussions, which is to the following effect:

"4. According to the learned Single Judge, clause XXIII of the settlement states about the daily rated workers who were appointed after they were given appointment by PSC. No such restrictions are mentioned in the above settlement clause or government order. When there is no ambiguity in the wordings in the settlement, it has to be literally interpreted. The court cannot assume hidden meanings so as to deny the benefits granted by the settlement. The wordings in the settlement are very clear. There is no room for any doubt. In fact, it is very clearly stated in the settlement that the daily wage period will be counted as qualifying service. The learned single Judge also referred to the decision of another single Bench of this Court reported in

There, the court said that a provisional employee is not entitled to pension. That is very clear also from rule 4 part III KSR that a provisional employee is not entitled to pension. In W.A.No.1975 of 1999 also, petitioners retired as provisional employees and they reached the age of superannuation before regularization. If a provisional employee retires as a provisional employee, he will not get pension. But, here, all the petitioners were provisional employees prior to 1994 and became regular employees much before 01.10.1994. Hence, they are entitled to get the benefit claimed as per the Government Order referred above. A cut off date is not mentioned in the settlement. Petitioners are entitled to the benefits of the settlement which the Corporation cannot avoid. In

the Apex Court reiterated the view that terms of settlement are binding on the workmen and union till it is terminated as provided under the Industrial Disputes Act and even the standing orders under the Standing Orders Act cannot be amended contrary to the terms of settlement. Binding nature of settlement is again reiterated by the Apex Court in

In the above circumstances, we direct the KSRTC to count the provisional service of the petitioners also as qualifying service for calculating pension and weightage if it is not already calculated."

24. It is relevant to note that against the above Division Bench judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra), the KSRTC filed a Special Leave to Appeal, which was dismissed by the Apex Court by its judgment dated 27.2.2006. The judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) was delivered on 1.6.2005. The KSRTC thereafter issued a circular dated 8.6.2006 purporting to clarify the expression and intention of clause XXIII of 1999 agreement to the effect that the clause only counts the daily wage period service rendered after appointment through PSC/Employment Exchange excluding the daily wage of the empanelled service.

25. The same issue came up for consideration before another Division Bench in W.A.No.2243 of 2006 and connected cases (KSRTC v. B.Mohanan Nair). The KSRTC tried to wriggle out from the judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) relying on the clarification, but the Division Bench in B.Mohanan Nair's case (supra) again reiterated and followed Idicula Abraham's case (supra). It is useful to note the issues, which came up for consideration before the Division Bench in the above case. In paragraph 1 of the judgment in B.Mohanan Nair's case (supra) the issues as well as clause XXIII of the settlement were quoted, which is to the following effect:

"In these appeals by the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (for short 'the Corporation') the question to be decided by us is "whether daily wage service', that an incumbent did have as Conductor/driver, shall be counted for the purpose of grant of retiral benefits on his retirement on superannuation after having been regularly appointed".

The issue is no longer res integre, in the light of the Division Bench judgment reported in

Idicula Abrham v. Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (2005 (3) KLT SN 67, Case No.79)

Referring to Clause XXIII of the settlement arrive at by the management of the Corporation and the employees of the Corporation - Ext.P16 in W.P.(C) No.26178/06 leading to W.A. No.2244/06, it has been held therein that the Corporation cannot refuse to count the daily wage service. The said settlement reads as follows :

"XXIII-pension:- 1. Pension will be paid as per the provisions of Kerala Service Rules followed by the Government from time to time.

2. Service under State Government prior to joining the Corporation will qualify for pension provided the break between Government service and Kerala State Road Transport Corporation service shall not exceed three months.

3. Daily wages period of Conductors, and Mechanical Staff before their regular appointment in full, will count for pension there should be at least ten days duty in a month. If there is no duty in a month, that month will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below ten or 50% of the total daily wage period excluding the months having no duty which ever is beneficial to the employees.

4. Pre-appointment training period of Mechanical Staff including Assistant Depot Engineers will be treated as qualifying service for pension."

In paragraphs 2, 3 and 4 of the same judgment the following was laid down:

"2. Though it has been thus stated tat the outset that Pension Rules in the KSR would be applicable, it had been amplified by Clause (3) of Settlement which provides for counting of daily wage period to '/Conductors/Mechanical Staff before their regular appointment in full with the condition that there should have been at least 10 days of duty in a month. Even if there is dearth of 10 days duty, it was further stated that the period during which there is such dearth will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below 10 or 50% of the total daily wage period excluding the months having no duty, whichever is beneficial to the employee. Thus, there is a binding provision in the settlement as provided for in Clause XXIII (3) of the Settlement to count daily wage service also for the purpose of retirement benefits.

3. Admittedly, all the petitioners in the writ petitions, except that in W.P.(C) No.33819/05 which leads to W.A. No.2243/06, were regularized in the service of the Corporation by the Order, taking into account the long tenure of daily wage employees, 699 Conductors and 6 painters were regularized in the service of the Corporation. After such regularization, on their retirement, Clause XXIII of the settlement as referred to above operate to count their daily wage service for computation of retiral benefits. Necessarily, the contention of the Corporation, that the settlement was arrive at far earlier than the regularization and such regularization was not in contemplation, is of no avail. Going by Section 18(3) (d) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, a settlement will be binding even on the future employees, unless it is terminated in accordance with law as provided in Section 19 of the said Act. No piece of evidence has been brought to our notice regarding the termination of the settlement. Necessarily, that will be binding to the employees regularized far later. Even if there had been any difficulty or inconvenience because of this mass regularization and consequent counting of their daily wage service prior to their regularization, it was incumbent on the Corporation in incorporate such restrictive covenant as a pre-condition for regularization. That has not been done or even no steps were taken to terminate the settlement. Therefore, the Corporation cannot revert back from the settlement and contend that the writ petitioners cannot seek to count the daily wage service put in by them before regularization for the purpose of retiral benefits in the light of the said clause in the settlement.

4. As regards the petitioner in W.P.(C) No.33819/05 leading to W.A. No.2243/06, he was a person appointed on daily wages as per Ext.P1 dated 24.2.1993 and was later regularized on advice by the P.S.C. As per Ext.P2 dtd. 07.07.2000. His case is also squarely covered by Clause XXIII of the settlement. Therefore, the learned Single Judge was perfectly justified in directing th Corporation to count the provisional service put in by him for the purpose of calculating his retiral benefits. This point is also covered in favour of the respondents in terms of the decision in Idicula Abraham's case (cited supra), which had been confirmed by the Supreme Court as well, refusing leave to appeal at the instance of the appellant/Kerala State Road Transport Corporation."

26. After the Division Bench judgment dated 18.12.2006 in B.Mohanan Nair's case (supra), the KSRTC implemented both the judgments ie., Idicula Abraham's case (supra) as well as B.Mohanan Nair's case (supra). It is useful to quote the order of the KSRTC dated 27.1.2007, which has been brought on record by the KSRTC itself as Exhibit P8 in W.A.No.150 of 2010, which is quoted as below:

"Sri. Idiculla Abraham, Driver retired from KSRTC in the AN of 30.4.02 had filed O.P.No.32977/12 for a direction to the KSRTC to count Employment Exchange service rendered by him prior to his regularization of appointment in the advise of KPSC as qualifying service for pension. The Hon'ble High Court of Kerala dismissed his petition and held that Clause XXIII(3) of the settlement arrived at by the Management and the employees of the Corporation is applicable only in the case of employees appointed as daily wage through PSC and Employment Exchange daily wage service cannot be counted for pension. Aggrieved by this, the petitioner filed W.A. No.1636/13 before the Hon'ble High Court. In this WA the Hon'ble Division Bench reversed the order of the learned Single Judge and observed that the wordings in the settlement are very clear and that it was very clearly stated in the settlement that daily wages period will be counted as qualifying service for pension. It was also observed that no restrictions are mentioned in the settlement that the Clause will be applicable only to those workers who were given appointment by PSC. On the above grounds the Division Bench directed the KSRTC to count provisional service of the petitioner as qualifying service for pension and weightage. Corporation preferred SLP against this judgment. However the Hon'ble Supreme Court dismissed the SLP. Thereafter following the advise of our standing counsel at Supreme Court, Corporation issued a circular memorandum on 8.6.06 clarifying that the spirit and intention of Clause XXIII(3) of 1999 agreement is only to count daily wage period of service rendered after appointment through PSC/Compassionate employment scheme excluding the daily wage Employment Exchange/Empanel service. The judgment rendered on the basis of the decision in the Idiculla Abraham's Case were challenged in appeal by the Corporation on the basis of the Clarification issued on 8.6.2006. But the Hon'ble High Court was not inclined to accept out contentions and the Writ Appeals were also dismissed by the common judgment dt. 18.12.06 in Writ Appeal No.2279/16 and connected cases. Opinion of our standing counsel at High Court regarding the scope of filing SLP was also sought. He opined that any clarification or amendment in the memorandum of settlement executed between KSRTC and recognized unions could be done only with the consent of all the parties to the agreement and that the clarification issued by the KSRTC is unilateral and not binding on the workmen. According to him, there is no scope for a successful appeal before the Supreme Court as no substantial question of Law is involved in the judgment in the Writ Appeals. Having considered all the above aspects in detail, Corporation is pleased to issue orders to count daily wage service rendered by Conductors, and Mechanical staff appointed through Employment Exchange as qualifying service for pension subject to the restrictions laid down in Clause XXIII(3) of the agreement dt.13.4.1999. In view of Clause X of the agreement this Order will be applicable only to those who retired from service on or after 1.2.99."

27. Thus, the KSRTC issued order to count daily wage services rendered by the Conductors, Drivers and Mechanical staff appointed through the Employment Exchange as qualifying service for the purpose of pension, subject to the condition laid down in clause XXIII-3.

28. The judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) was referred for consideration before a Full Bench. The Full Bench of this court decided the controversy in Kunchan's case (supra), the correctness of which judgment is referred for consideration before this Larger Bench. The Full Bench itself has noted the two issues, which arose for consideration before the Full Bench, which were noted in paragraph 1 of the judgment in Kunchan's case (supra), which is to the following effect:

"1. The issues that have been formulated for consideration by the Full Bench can be, as a matter of convenience, encapsulated as hereunder:

(1) Whether the service as a daily wage employee rendered by a person, at the instance of the employer, after he has been selected for regular appointment by the Public Service Commission (for short 'the Commission') and duly advised in that regard, can be taken as qualifying service for the purpose of pension and other retirement benefits?

(2) As a corollary, does the service rendered as a daily wage employee or a casual employee in an organization, where the Kerala Service Rules have been adopted for all relevant purposes, in circumstances other than what is mentioned in Issue No. 1 above, be eligible to be treated as qualifying service for the purpose of pension?"

The facts of the case before the Full Bench were that the petitioner, after advice by the PSC, was appointed by the KSRTC as Driver on daily wages. He was later absorbed in regular service and retired, when the KSRTC declined to count the services rendered by him as a daily wage employee in the same post, he filed the Writ Petition for appropriate direction. The learned Single Judge allowed the Writ Petition, against which Writ Appeal was filed. The petitioner relied on Division Bench judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra). The Bench hearing the Writ appeal took a different view and made a reference to the Larger Bench. In the above case, after advice by the Commission for regular recruitment in favour of the petitioner, he could be appointed as reserve Driver on 30.5.1989 and he could commence regular service under order dated 7.6.1990 only and he was absorbed in the post of Driver Grade-II. The petitioner retired on 31.8.1998. The dispute is related to a manner in which his period from 30.5.1989 till he was appointed on regular service with effect from 21.3.1990 was to be treated with. The Full Bench answered Issue No.(1) holding that he will be entitled to reckon the above period for the purpose of pension. Answer to the above issue is in paragraph 20, which is quoted as below:

"20. We are, therefore, of the definite view that the entirety of the services rendered by the writ petitioner with effect from 30/05/1989 till the date of his retirement on 31/08/1998 is eligible to be treated as qualifying service for the purpose of pension and other retirement benefits. Consequently, the writ petitioner would also be entitled to the benefits that are due to a retired employee as per the long term settlement arrived at between the Corporation and the workers on 13/04/1999. We also take note of the fact that a Bench of this Court had, in WA No. 3146/01, declared that employees, who retire between 01/03/1997 and 31/10/1999 are entitled not only to the revised monthly pension, but also other pensionary benefits such as Death Cum Retirement Gratuity, Commuted Value of Pension etc., subject to eligibility at the revised rate."

29. Now coming to Issue No.(2), the Full Bench did not follow Idicula Abraham's case (supra) and relying on the judgment of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) it held that the period of daily wage of any other kind cannot be reckoned for pensionary purpose. It was further held that the Corporation, an instrumentality of the State, cannot be considered as having agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles, hence the term of settlement has to be treated only such casual service who has already been advised by the Commission. The following was laid down in paragraphs 24, 25, 26 and 27 of the judgment:

"24. The Supreme Court in Umadevi was essentially concerned with the question of regularisation of persons, who were appointed on a casual or ad hoc basis. It was contended on behalf of casual employees seeking regularisation, that persons who are appointed in public service otherwise than by following the notified and established system of selection and appointment and who have continued for long period in such capacity should be treated as entitled to regularisation in service, as a recognition of their right under Art.14, 16 and 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court held that adherence to the principles of equality is a basic feature of our Constitution and since the rule of law is the core of our Constitution, the Court would certainly be disabled from passing an order upholding the violation of Art.14 or in overlooking the need to comply with the requirement of Art.14 read with Art.16 of the Constitution. The following observations made by the Supreme Court in paragraph 43 of the judgment is apposite in this context:

'43. Thus, it is clear that adherence to the rule of equality in public employment is a basic feature of our Constitution and since the rule of law is the core of our Constitution, a Court would certainly be disabled from passing an order upholding a violation of Art.14 or in ordering the overlooking of the need to comply with the requirements of Art.14 read with Art.16 of the Constitution. Therefore, consistent with the scheme for public employment, this Court while laying down the law, has necessarily to hold that unless the appointment is in terms of the relevant rules and after a proper competition among qualified persons, the same would not confer any right on the appointee. If it is a contractual appointment, the appointment comes to an end at the end of the contract, if it were an engagement or appointment on daily wages or casual basis, the same would come to an end when it is discontinued. Similarly, a temporary employee could not claim to be made permanent on the expiry of his term of appointment. It has also to be clarified that merely because a temporary employee or a casual wage worker is continued for a time beyond the term of his appointment, he would not be entitled to be absorbed in regular service or made permanent, merely on the strength of such continuance, if the original appointment was not made by following a due process of selection as envisaged by the relevant rules. It is not open to the Court to prevent regular recruitment at the instance of temporary employees whose period of employment has come to an end or of ad hoc employees who by the very nature of their appointment, do not acquire any right. The High Courts acting under Art.226 of the Constitution, should not ordinarily issue directions for absorption, regularisation, or permanent continuance unless the recruitment itself was made regularly and in terms of the constitutional scheme. Merely because an employee had continued under cover of an order of the Court, which we have described as 'litigious employment' in the earlier part of the judgment, he would not be entitled to any right to be absorbed or made permanent in the service. In fact, in such cases, the High Court may not be justified in issuing interim directions, since, after all, if ultimately the employee approaching it is found entitled to relief, it may be possible for it to mould the relief in such a manner that ultimately no prejudice will be caused to him, whereas an interim direction to continue his employment would hold up the regular procedure for selection or impose on the State the burden of paying an employee who is really not required. The Courts must be careful in ensuring that they do not interfere unduly with the economic arrangement of its affairs by the State or its instrumentalities or lend themselves the instruments to facilitate the bypassing of the constitutional and statutory mandates.'

25. The Court held in categoric terms that appointments made otherwise than in accordance with the procedure notified for the public service in question are irregular appointments and an appointee rendering service on the basis such irregular appointment cannot, in law, claim parity with the regular employee. Such irregular appointments cannot be regularised as it would tantamount to regularizing back door or irregular appointments. This, the Supreme Court held, would be unconstitutional, apart from being illegal, as being violative of Art.14 and 21 of the Constitution.

26. Keeping the aforementioned law laid down by the Supreme Court in the background, can it be said that casual service or daily rated service by an employee, should, in all circumstances, be treated as regular service to be so reckoned for all intents and purposes? As we have held above, the nomenclature of the service rendered by a person advised by the Commission to a post forming part of the regular cadre service in the Corporation is not decisive. His service will have to be treated as regular service. This is because his entry into service, is not through the back door but by a regular legitimate process laid down in that behalf. It will not be open to the Corporation to appoint a person who has been advised by the Commission as casual employee because it suited the Corporation to do so. But, at the same time, it might even be necessary for the Corporation to appoint persons on a casual or daily wage basis. This administrative exigency is recognised by the Supreme Court in Umadevi as well. Such service is treated only as casual service and the fact that the said employee was later absorbed into regular service, after being found eligible in a due process of selection, cannot transform the earlier casual service rendered by him as a regular service. To recognise such a principle would, in effect, be a regularisation of an irregular appointment, which, as the Supreme Court held in Umadevi is anathema in the constitutional scheme of appointments in public service. Obviously, the direction to treat such casual service as regular service would mean that the employee concerned would be entitled to treat his entry into service as commensurate with the commencement of casual service.

27. For the reasons mentioned above, we are of the view that the principle laid down in Idicula, to the extent to which directs that any kind of casual service of an employee, followed by an entry of such employee in regular service would be eligible to be treated as regular service for all intents and purposes does not lay down the correct principle. No doubt, the Bench in Idicula was essentially trying to construe a term contained in the conciliation settlement between the management and the employees. But, we cannot, but take note of the fact that regular selection and appointment of persons in the Corporation has been done for the past 30 years, only on the advice of the Commission. The Corporation, an instrumentality of the State, cannot be considered as having agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles that should invariably govern the affairs of an instrumentality of the State. Thus, where a term of settlement, to which an instrumentality of a State is a party, provides for treating casual service also as part of regular service for all intents and purposes, then it will only be appropriate to treat only such casual service, rendered by a person, who has already been advised by the Commission for regular appointment against the post in question as part of regular service. Any other kind of casual service would only be casual service, that cannot be considered as synonymous with regular service. We hold that the contrary principle laid down in Idicula does not lay down the correct law."

30. From the judgment of the Full Bench in Kunchan's case (supra) it is clear that the Full Bench has referred to and relied on the settlement arrived between the KSRTC and employees Association on 13.4.1999, following which it was held that the petitioner was entitled to reckon his service with effect from 30.5.1989. The Full Bench found support for its decision from the judgment of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra). Paragraph 43 of the judgment in Umadevi's case (supra) specifically referred to and relied on by the Full Bench. The Full Bench, after referring to paragraph 43 of the judgment in Umadevi's case (supra), laid down in paragraph 25 that appointments made not in accordance with the procedure notified for the public service in question are irregular appointments and an appointee rendering service on the basis of such irregular appointment cannot, in law, claim parity with the regular employee. The Full Bench further held that irregular appointments cannot be regularised as it would tantamount to regularising back door or irregular appointments. The Full Bench in paragraph 27 opined that the ratio of principle laid down in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) to the extent to which it directs that any kind of casual service of an employee, followed by an entry of such employee in regular service would be eligible to be treated as regular service for all intents and purposes does not lay down the correct principle. The Full Bench also noted that the Bench in Idicula Abraham's case (supra) has referred to the terms contained in the settlement between the management and the employees. The Full Bench has made the following observations for disapproving the Division Bench judgment in Idicula Abraham's case (supra):

"......The Corporation, an instrumentality of the State, cannot be considered as having agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles that should invariably govern the affairs of an instrumentality of the State. Thus, where a term of settlement, to which an instrumentality of a State is a party, provides for treating casual service also as part of regular service for all intents and purposes, then it will only be appropriate to treat only such casual service, rendered by a person, who has already been advised by the Commission for regular appointment against the post in question as part of regular service. Any other kind of casual service would only be casual service, that cannot be considered as synonymous with regular service. We hold that the contrary principle laid down in Idicula does not lay down the correct law."

31. The Full Bench judgment in Kunchan's case (supra) is based on the following two main reasons:

(a) the Apex Court having held in Umadevi's case (supra) that daily wage employees, who were not appointed following regular process of public employment cannot be regularised in service, and such service is treated only as casual service and the fact that such employees were later absorbed in regular service after being found eligible in due process of selection cannot transform the earlier casual service rendered by him as a regular service. To recognise such a principle would, in fact, be a regularisation of an irregular appointment, which, as the Supreme Court held in Umadevi's case (supra) is anathema in the constitutional scheme of appointments in public service;

(b) The Corporation, an instrumentality of the State, cannot be considered as having agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles that should invariably govern the affairs of an instrumentality of the State. Thus, where a term of settlement, to which an instrumentality of a State is a party, provides for treating casual service also as part of regular service for all intents and purposes,then it will only be appropriate to treat only such casual service, rendered by a person,who has already been advised by the Commission for regular appointment against the post in question as part of regular service. Any other kind of casual service would only be casual service, that cannot be considered as synonymous with regular service.

32. Thus, we have to test as to whether the above two reasons given by the Full Bench for a decision lay down correct proposition of law. We have to consider the judgment of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) and to examine as to whether the said judgment has been correctly relied on by the Full Bench for the propositions as laid down by the Full Bench. In the Umadevi's case one of the respondents were temporarily engaged on daily wages in the Commercial Tax Department in the State of Karnataka. The employees raised the claim that they have worked in the department based on daily wage engagement for more than 10 years, hence they are entitled to be permanent employees of the department. The Government did not accede to the request of the employees. The employees approached the Administrative Tribunal, which rejected their claim, the employees filed a Writ Petition in the High Court and the High Court directed that they are entitled to wages equal to the salary and allowances that are being paid to the regular employees of their cadre in Government service with effect from the dates from which they were respectively appointed. The High court also directed to consider their cases for regularisation within a period of four months. The order of the High Court was challenged by the State of Karnataka before the Apex Court. The Apex Court noticed that in the matter of regularisation of ad hoc employees, there were conflicting decisions by three Judge Bench of the Apex Court and by two Judge Bench and hence the question was referred to be considered by a Larger Bench. It is relevant to note that in Umadevi's case (supra) itself the Constitution Bench has recognised the right of the State or its instrumentality to employ persons in the posts which are in temporary or daily wages or additional hands to discharge the duties. The Constitution Bench, after referring various judgments held that merely because a temporary employee or a casual wage worker is continued for a time beyond the term of his appointment, he would not be entitled to be absorbed in regular service or made permanent. The following was laid down in paragraph 43 of the judgment:

"43. ....... It has also to be clarified that merely because a temporary employee or a casual wage worker is continued for a time beyond the term of his appointment, he would not be entitled to be absorbed in regular service or made permanent, merely on the strength of such continuance, if the original appointment was not made by following a due process of selection as envisaged by the relevant rules. It is not open to the court to prevent regular recruitment at the instance of temporary employees whose period of employment has come to an end or of ad hoc employees who by the very nature of their appointment, do not acquire any right. The High Courts acting under Article 226 of the Constitution, should not ordinarily issue directions for absorption, regularisation, or permanent continuance unless the recruitment itself was made regularly and in terms of the constitutional scheme. Merely because an employee had continued under cover of an order of the court, which we have described as "litigious employment" in the earlier part of the judgment, he would not be entitled to any right to be absorbed or made permanent in the service. In fact, in such cases, the High Court may not be justified in issuing interim directions, since, after all, if ultimately the employee approaching it is found entitled to relief, it may be possible for it to mould the relief in such a manner that ultimately no prejudice will be caused to him, whereas an interim direction to continue his employment would hold up the regular procedure for selection or impose on the State the burden of paying an employee who is really not required. The courts must be careful in ensuring that they do not interfere unduly with the economic arrangement of its affairs by the State or its instrumentalities or lend themselves the instruments to facilitate the bypassing of the constitutional and statutory mandates."

33. In paragraph 53 of the judgment, the Apex Court further laid down that regularisation already made be not reopened unless the matter was subjudice. The following are the observations made in paragraph 53 of the judgment:

"53. One aspect needs to be clarified. There may be cases where irregular appointments (not illegal appointments) as explained in S.V. Narayanappa, R.N. Nanjundappa and B.N. Nagarajan and referred to in para 15 above, of duly qualified persons in duly sanctioned vacant posts might have been made and the employees have continued to work for ten years or more but without the intervention of orders of the courts or of tribunals. The question of regularisation of the services of such employees may have to be considered on merits in the light of the principles settled by this Court in the cases above referred to and in the light of this judgment. In that context, the Union of India, the State Governments and their instrumentalities should take steps to regularise as a one-time measure, the services of such irregularly appointed, who have worked for ten years or more in duly sanctioned posts but not under cover of orders of the courts or of tribunals and should further ensure that regular recruitments are undertaken to fill those vacant sanctioned posts that require to be filled up, in cases where temporary employees or daily wagers are being now employed. The process must be set in motion within six months from this date. We also clarify that regularisation, if any already made, but not subjudice, need not be reopened based on this judgment, but there should be no further bypassing of the constitutional requirement and regularising or making permanent, those not duly appointed as per the constitutional scheme."

34. The Apex Court allowed the appeal filed by the State of Karnataka, but it was further observed that regular recruitment be undertaken and in the said regular recruitment the respondents will be allowed to compete by giving the age relaxation.

35. Umadevi's case (supra) was a case where the Apex Court was considering the question of regularisation of daily rated temporary employee, who were appointed de horse the statutory rules. The Apex Court held that the employees appointed on daily wages are not entitled to regularisation in service and their regularisation shall be violative of Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of India and the High Court in exercise of jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution shall not issue any direction for regularisation of such employees. It is further relevant to note that the Apex Court itself specifically directed that regularisation already made shall not be reopened based on the said judgment.

36. Present is not a case of regularisation of daily wage employees by the KSRTC. Persons who were appointed initially on daily wage basis were subsequently regularly appointed on the basis of advice given by the PSC. The regularisation of such employees was never questioned by any one including the KSRTC, nor in the Writ Petition giving rise to this Writ Appeal the issue of regularisation of such employees was in question. The question which had arisen in the Writ Petition was as to whether the period during which the petitioner had worked as Daily wage Driver in the KSRTC before his regular appointment in the KSRTC should be reckoned for the purpose of pension or not. The Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) has neither considered any such question nor the said judgment can be treated to have laid down any proposition that period of a daily wage employee, who was subsequently regularly appointed, cannot be reckoned for the purpose of pension. Whether the services rendered by an employee in different categories are entitled to be reckoned for pension is essentially a matter of statutory rules and orders of the State Government and the employer. Since no such issue has come up before Umadevi's case (supra), we are of the view that the judgment of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) was not applicable on the issues which arose before the Full Bench in Kunchan's case (supra).

37. The Apex Court has laid down in

Ambika Quarry Works v State of Gujarat and others [(1987)1 SCC 213]

that the ratio of a decision must be understood in the background of facts of that case. The following observations are made in paragraph 18 of the judgment:

"18. xx xx xx

The ratio of any decision must be understood in the background of the facts of the case. It has been said long time ago that a case is only an authority for what it actually decides, and not what logically follows from it. (See Lord Halsbury in Quinn v. Leathem). But in view of the mandate of Article 141 that the ratio of the decision of this Court is a law of the land, Shri. Gobind Das submitted that the ratio of a decision must be found out from finding out if the converse was not correct."

"59. A decision, as is well known, is an authority for which it is decided and not what can logically be deducted therefrom. It is also well settled that a little difference in facts or additional facts may make a lot of difference in the precedential value of a decision.[See Ram Rakhi v. Union of India, Delhi Admn. (NCT of Delhi) v. Manohar Lal, Haryana Financial Corpn. v. Jagadamba Oil Mills and Nalini Mahajan (Dr) v. Director of Income Tax (Investigation)]"

39. The Apex Court in

Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. and another v. N.R.Vairamani and another [(2004)8 SCC 579]

has held that the judgments of the Court are not to be construed as statutes and the observations must be read in the context in which they appear to have been stated. Following was laid down in paragraph 9 to 12:

"9. Courts should not place reliance on decisions without discussing as to how the factual situation fits in with the fact situation of the decision on which reliance is placed. Observations of courts are neither to be read as Euclid's theorems nor as provisions of a statute and that too taken out of their context. These observations must be read in the context in which they appear to have been stated. Judgments of courts are not to be construed as statutes. To interpret words, phrases and provisions of a statute, it may become necessary for judges to embark into lengthy discussions but the discussion is meant to explain and not to define. Judges interpret statutes, they do not interpret judgments. They interpret words of statutes; their words are not to be interpreted as statutes. In London Graving Dock Co. Ltd. v. Horton (AC at p. 761) Lord MacDermott observed: (All ER p. 14 C-D)

"The matter cannot, of course, be settled merely by treating the ipsissima verba of Willes, J., as though they were part of an Act of Parliament and applying the rules of interpretation appropriate thereto. This is not to detract from the great weight to be given to the language actually used by that most distinguished judge,..."

10. In Home Office v. Dorset Yacht Co. (All ER p. 297g- h) Lord Reid said,

"Lord Atkin's speech ... is not to be treated as if it were a statutory definition. It will require qualification in new circumstances".

Megarry, J. in Shepherd Homes Ltd. v. Sandham (No.2) observed:

"One must not, of course, construe even a reserved judgment of Russell, L.J. as if it were an Act of Parliament."

And, in Herrington v. British Railways Board Lord Morris said: (All ER p. 761c)

"There is always peril in treating the words of a speech or a judgment as though they were words in a legislative enactment, and it is to be remembered that judicial utterances made in the setting of the facts of a particular case."

11. Circumstantial flexibility, one additional or different fact may make a world of difference between conclusions in two cases. Disposal of cases by blindly placing reliance on a decision is not proper.

12. The following words of Lord Denning in the matter of applying precedents have become locus classicus: "Each case depends on its own facts and a close similarity between one case and another is not enough because even a single significant detail may alter the entire aspect, in deciding such cases, one should avoid the temptation to decide cases (as said by Cardozo) by matching the colour of one case against the colour of another. To decide therefore, on which side of the line a case falls, the broad resemblance to another case is not at all decisive. * * * Precedent should be followed only so far as it marks the path of justice, but you must cut the dead wood and trim off the side branches else you will find yourself lost in thickets and branches. My plea is to keep the path to justice clear of obstructions which could impede it."

40. In view of the law laid down in the above cases on the law of precedent, we are of the considered opinion that the judgment of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) was not applicable and the Full Bench committed an error in treating the ratio of the Apex Court in Umadevi's case (supra) applicable in the present case.

41. Now we come to the second reason given by the Full Bench judgment as noted above that the KSRTC, an instrumentality of the State, cannot be considered to have agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles. Full Bench further held that where the 'settlement' provided for treating casual service also as part of regular service for all intents and purposes, then it will only be appropriate to treat only such casual service rendered by a person, who has already been advised by the PSC for regular appointment against the post in question as part of regular service. The above observations were made by the Full Bench in the context of settlement dated 13.4.1999 entered between the KSRTC and its employees. It is again useful to refer to clause XXIII-3 of the settlement, which is to the following effect:

"XXIII-3. Daily wages period of Conductors, Drivers and Mechanicals Staff before their regular appointment in full, will count for pension provided there should be at least ten days duty in a month. If there is no duty in a month, that month will be excluded and 50% will be taken as qualifying service of the months in which the number of duty is below 10 or 50% of the total daily wage period excluding the months having no duty whichever is beneficial to the employee."

Clause XXIII-3 uses the words "daily wages period of Conductors, Drivers and Mechanical Staff before their regular appointment in full". The said clause do not contain any such pre-condition that the said daily wage period of Drivers should be after they have been advised by the PSC for regular appointment. In fact, the interpretation, which the Full Bench has put to the aforesaid clause runs counter to the plain meaning of the settlement. The use of the words "before their regular appointment in full" clearly indicate that daily wage period referred to is before regular appointment. The Full Bench has put the interpretation as noted above by observing that the KSRTC cannot be considered to have agreed to any settlement which will not bear true allegiance to the constitutional principles. We fail to see that by entering into the above settlement, by giving the benefit of daily wage period prior to regular appointment for the purpose of pension, how the settlement is unconstitutional.

42. As noted above, Rule 11 of the Kerala Service Rules itself contemplates reckoning of any period of a specified service by an order issued by the State Government. It is relevant to note that although the settlement covered about 161 categories of employees, the fact of reckoning of daily wage period was confined to three categories, i.e., Conductors, Drivers and mechanical staff, which was with some purposes and objects. The settlement contemplated by Section 18(1) of the Industrial Disputes Act is a voluntary settlement arrived between the employer and workmen. The settlement continues to be binding on the employees and employer till its effect is taken away as per Section 19(2) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. In the present case, it is not the case of the KSRTC that the settlement is not binding. But the KSRTC is interpreting clause XXIII-3 in a manner as to confine the benefit to one particular category of daily wage employees, which is not in any manner indicated in the settlement. The observation of the Full Bench in paragraph 27 of the judgment that the State should not have been considered to have agreed to the settlement is of no consequence. The settlement was, in fact, entered, and will be binding between the parties. The Full Bench, while interpreting the settlement, has put certain restrictions by adding words to the settlement which were never contemplated.

43. The Apex Court had occasion to consider Section 18(1) of the Industrial Disputes Act in

Herbertsons Ltd. v. Workmen (AIR 1977 SC 322)