(2015) 393 KLW 110

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM

PRESENT: THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE BABU MATHEW P.JOSEPH

TUESDAY, THE 11TH DAY OF NOVEMBER 2014/20TH KARTHIKA, 1936

WP(C).No. 1329 of 2010 (Q)

PETITIONERS

1. C.K.SATHIANATHAN, CHIEF MANAGER, INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK, REGIONAL OFFICE, 3RD FLOOR RACHANA BUILDING, RAJENDRA PLACE, NEW DELHI-110008.

2. K.V.JAINE,MANAGER,INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK, REGIONAL OFFICE, VETTUKATTIL BUILDINGS, M.G.ROAD ERNAKULAM-682 016.

BY ADVS. SRI.K.RAMAKUMAR (SR.) SRI.T.RAMPRASAD UNNI SMT.SMITHA GEORGE

RESPONDENTS

1. THE CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION KOCHI, REP.BY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KATHRIKKADAVU KOCHI.

2. SRI.A.P.SINGH,GENERAL MANAGER,INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK, CENTRAL OFFICE, 763 ANNA SALAI, CHENNAI-2.

3. THE INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK,CENTRAL OFFICE, 763, ANNA SALAI, CHENNAI-2 REP., BY ITS MANAGING, DIRECTOR.

4. THE CENTRAL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICER, RTI CELL, LAW DEPARTMENT, INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK CENTRAL OFFICE, 763, ANNA SALAI CHENNAI-2.

R1 BY ADV. SRI.P.CHANDRASEKHARA PILLAI, C.B.I. R3 BY ADV. SRI.LEO GEORGE,SC,INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK

JUDGMENT

The petitioners challenge Ext.P1 order dated 26-10-2009 passed by the second respondent, who is the General Manager, Indian Overseas Bank, Central Office, Chennai, according sanction under

Section 19(1)(c) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

(PC Act) for prosecuting the petitioners and another for certain criminal offences.

2. The facts which are necessary for disposing of this writ petition are briefly stated as follows:

The first petitioner is working as a Chief Manager and the second petitioner is working as a Manager in the Indian Overseas Bank, a nationalised bank. While they were working in the main branch of the Bank at Ernakulam from 2006 to 2009, they had advanced a loan of 100 lakh to M/s Karma Constructions, a proprietary concern of Sri.Binoy K. Ravindran, a businessman, after due enquiries and as a pure commercial transaction. Before releasing the loan amount, prior sanction from the regional office of the Bank was also obtained. The transaction was perfectly transparent supported by application and collateral security. But, it was alleged that the loanee misused the loan for purposes other than the purpose for which the loan was availed off. The first respondent, Central Bureau of Investigation (for short, the CBI), based on some 'source information', registered FIR No.RC 2(A)/2009 of CBI/SPE/Cochin on 25-03-2009 against the petitioners and the said Sri.Binoy K. Ravindran alleging the commission of offences under Section 120B read with Section 420 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and under Section 13(2) read with Section 13(1)(d) of the PC Act raising various allegations in respect of the loan sanctioned. Later, after investigation, the Superintendent of Police, CBI, SPE, Cochin, sent a letter dated 24-07-2009 requesting the second respondent for his sanction to prosecute the petitioners and another officer of the Bank for the said offences. The request was accompanied by a detailed report of the Superintendent of Police, CBI, Cochin. The second respondent, after considering the report of the CBI and the office note of the Vigilance Department of the Bank in respect of the matter, finding that the ends of justice would be met by taking departmental action against the petitioners and another for the procedural lapses committed by them and there was no need to give sanction for prosecution by the CBI unless any new facts come to light, declined to accord sanction for prosecution by order dated 24-09-2009 and directed to inform the CBI accordingly.

3. Thereafter, the Superintendent of Police, CBI, sent a letter dated 13/15-10-2009 to the second respondent requesting him to review the order dated 24-09-2009 declining to grant sanction for prosecution and to grant sanction for prosecution. Accordingly, the second respondent has issued Ext.P1 order dated 26-10-2009 according sanction for prosecution of the petitioners and another for the said offences. The petitioners challenge Ext.P1 raising various grounds.

4. Heard Sri.K.Ramkumar, the learned Senior Counsel appearing for the petitioners, Sri.P.Chandrasekhara Pillai, the learned Standing Counsel for the first respondent and Sri.Leo George, the learned counsel appearing for the respondents 2 to 4.

5. A statement has been filed on behalf of the first respondent disputing the contentions raised by the petitioners. A counter affidavit has been filed on behalf of the respondents 2 to 4 disputing the case of the petitioners and justifying the issuance of Ext.P1. As directed by this Court, the respondents 2 to 4 have made available the records of the case (some of them are copies and some others are original) for perusal by this Court.

6. Learned Senior Counsel for the petitioners mainly raised the following contentions challenging the validity of Ext.P1 order of sanction:

(1) The second respondent, after considering the report of the CBI and the office note furnished by the Vigilance Department of the Bank, arrived at a proper conclusion that departmental action would be sufficient for the procedural lapses committed by the petitioners and another and no sanction for prosecuting them need be granted. Such an order passed by the second respondent cannot be reviewed by him.

(2) A review of the order declining sanction for prosecution by the second respondent would have serious consequences affecting the petitioners. But, reviewing the earlier order, the second respondent passed the impugned Ext.P1 order without affording an opportunity of being heard to the petitioners violating the principles of natural justice.

(3) The CBI has not collected any further materials conducting investigation after passing the order by the second respondent declining sanction for prosecution. Therefore, no new materials were available for the second respondent to review the earlier order and granting sanction.

(4) Ext.P1 does not say that it is passed reviewing the earlier order for any reason whatsoever. Therefore, absence of application of mind is quite evident while passing Ext.P1.

(5) Ext.P1 was passed by the second respondent not based on his independent satisfaction that sanction should be granted. But, simply based on the pressure exerted by the CBI for reviewing the earlier order and for granting sanction. Therefore, the very basis of Ext.P1 is extraneous considerations and not cogent materials justifying it.

7. Learned Standing Counsel for the CBI, on the contrary, disputed all the contentions raised by the learned Senior Counsel for the petitioners. He submitted that the second respondent is competent to review his earlier order and to grant sanction for prosecution. In that process, the petitioners are not entitled to notice. According to him, there are various reasons enabling the Government or an administrative authority empowered to grant sanction under Section 19 of the PC Act to review the earlier order declining sanction. The second respondent has applied his mind while passing Ext.P1 order granting sanction. The allegation that the pressure exerted by CBI or extraneous considerations persuaded the second respondent to review his earlier order and pass Ext.P1 is incorrect. Ext.P1 has been issued by the second respondent independently exercising his power as the competent authority to issue such an order. The CBI has submitted the Final Report in the case along with Ext.P1 sanction order issued by the second respondent before the court and the court has taken cognizance of the offences on 04-11-2009. Since the court has taken cognizance of the matter, the petitioners can challenge the validity of Ext.P1 during the trial of the case in the court. They are not entitled to challenge the validity of Ext.P1 in this Court invoking Article 226 of the Constitution of India as in a case of absence of sanction, contended the learned Standing Counsel. Learned counsel for the respondents 2 to 4 also justified Ext.P1. Learned Senior Counsel for the petitioners as well as the Standing Counsel for the first respondent cited various rulings in support of their contentions.

8. I shall first deal with certain facts involved in this case before going into the contentions raised by the parties. The petitioners specifically averred in the writ petition that the sanction sought for by the CBI was refused by an order issued in September, 2009. Despite their request, the petitioners were not issued with a copy of that order. The CBI has kept mum in their statement, regarding the fact that their request for sanction was refused by the second respondent. It is also averred by the petitioners that the CBI sought for a review of the earlier order declining sanction and the second respondent, without any application of mind and without examining the settled legal position that there cannot be a review of an administrative order, granted sanction, even without referring to the initial rejection of sanction, by issuing Ext.P1. The CBI has not only kept mum about the earlier order passed by the second respondent, but also stated that it was wrong to say that the sanctioning authority reviewed his order. A perusal of the statement of the first respondent would go to show that they have not chosen to deal with the averments made by the petitioners in a clear and proper way. The records would show that the second respondent has declined sanction for prosecution finding that the ends of justice would be met by initiating departmental action against the petitioners and another for their procedural lapses. Also directed to inform the CBI accordingly. The CBI was accordingly informed that fact by letter dated 24-09-2009. It can also be seen from the records that, referring to the said letter dated 24-09-2009, the CBI requested, by their letter dated 13/15-10-2009, to review the earlier decision of the second respondent and to grant sanction for prosecution. Therefore, the petitioners cannot be blamed for their submission before this Court that the first respondent has not divulged the true facts before this Court in their statement. It was not disputed at the hearing by the CBI that the second respondent has declined to grant sanction for prosecution as per his order dated 24-09-2009. As already adverted to, such a fact is quite evident from the records produced before this Court.

9. I shall now deal with the contentions raised by the parties. Learned Senior Counsel for the petitioners, relying on the decision rendered by the Honourable Supreme Court in

Kuntesh v. Management, H.K. Mahavidyalaya, Sitapur (AIR 1987 SC 2186)

contended that the second respondent, being a quasi-judicial authority, cannot review his own order by which sanction for prosecution was declined. Reliance was placed on the following passage from the judgment:

"11. It is now well established that a quasi judicial authority cannot review its own order, unless the power of review is expressly conferred on it by the statute under which it derives its jurisdiction. The Vice-Chancellor in considering the question of approval of an order of dismissal of the Principal, acts as a quasi judicial authority. It is not disputed that the provisions of the U.P. State Universities Act, 1973 or of the Statutes of the University do not confer any power of review on the Vice-Chancellor. In the circumstances, it must be held that the Vice-Chancellor acted wholly without jurisdiction in reviewing her order dated January 24, 1987 by her order dated March 7, 1987. The said order of the Vice-Chancellor dated March 7, 1987 was a nullity."

The PC Act does not confer any power on the second respondent to review an order passed by him declining sanction for prosecution. Therefore, according to the learned Senior Counsel, Ext.P1 order granting sanction for prosecution passed by the second respondent is without any power and authority. This argument cannot be accepted for two reasons. (1) An authority exercising power under Section 19 of the PC Act is not a quasi-judicial authority, but only an administrative authority. In Kuntesh's case (supra), the Honourable Supreme Court was dealing with a case where the Vice Chancellor of the University had exercised jurisdiction as a quasi-judicial authority. Exercising that jurisdiction, as evident from the passage quoted, the Vice Chancellor passed an order in one way. Subsequently, that was reviewed by the Vice Chancellor. Since the U.P. State Universities Act or the Statutes of the University did not confer any power of review on the Vice Chancellor, the order passed by the Vice Chancellor was found to be a nullity in the judgment following the settled position of law that a quasi-judicial authority cannot review its own order unless the power of review is expressly conferred on it by the statute under which it derives its jurisdiction.

10. In the case on hand, the second respondent is not a quasi-judicial authority. He is only an administrative authority empowered to exercise the powers under Section 19 of the PC Act. The Honourable Supreme Court laid down in

State of Bihar v. P.P.Sharma (1992 Supp (1) SCC 222)

that the order of sanction is only an administrative act and not a quasi-judicial one nor is a lis involved.

11. The Honourable Supreme Court in a series of decisions laid down that the authority who passed the order exercising power under Section 19 of the PC Act or under other acts containing similar provisions can review its earlier order for various reasons. I shall deal with those reasons and decisions during the course of this judgment. One thing is certain. The authority exercising power to grant or not to grant sanction can review its decision for various reasons. Therefore, the contention that the second respondent is a quasi-judicial authority and hence he cannot review his order passed exercising powers under Section 19 of the PC Act is only to be rejected and I do so.

12. The contention raised on behalf of the petitioners that Ext.P1 order passed by the second respondent reviewing his earlier order is capable of causing serious consequences affecting the petitioners and hence before passing such an order, the second respondent should have given an opportunity of being heard to the petitioners is also equally unsustainable. The Honourable Supreme Court in P.P.Sharma's case (supra) laid down as follows:

"67. It is equally well settled that before granting sanction the authority or the appropriate Government must have before it the necessary report and the material facts which prima facie establish the commission of offence charged for and that the appropriate Government would apply their mind to those facts. The order of sanction is only an administrative act and not a quasi-judicial one nor is a lis involved. Therefore, the order of sanction need not contain detailed reasons in support thereof as was contended by Sri Jain. But the basic facts that constitute the offence must be apparent on the impugned order and the record must bear out the reasons in that regard. The question of giving an opportunity to the public servant at that stage as was contended for the respondents does not arise. .........."

The law thus laid down has been followed by the Supreme Court in

State Anti-Corruption Bureau v. P. Suryaprakasam [(2008) 14 SCC 13]

Therefore, the contention of violation of principles of natural justice also cannot be accepted.

13. The Superintendent of Police, CBI, Cochin, sent his detailed report on the matter along with his covering letter dated 24-07-2009 to the Bank requesting for sanction by the competent authority for prosecuting the petitioners and another. The report so sent contains all the details. The evidence collected from the witnesses also accompanied the report. The second respondent considered the report of the CBI and the office note dated 30-07-2009 of the Vigilance Department of the Bank and passed an order on 24-09-2009 declining sanction which reads as follows:

"I have gone through the CBI report and Office note dated 30.07.2009 of Vigilance Department in respect of the above case. Although CBI has requested for sanction for prosecution against Shri. C. K. Sathyanathan, Roll No. 33913, the then Chief Manager, Shri. K. V. Jaine, Roll No. 35705, Manager and Shri. N. Suresh, Roll No. 17509, the then senior Manager, I find that the lapses/ irregularities committed by the above named officials are mostly procedural in nature. I also observe that the Branch was able to recover Rs. 96.00 lacs under OTS without any write-off against release of the title deeds to property held by the Branch for the advances granted to M/s Karma Constructions, the proprietary concern of Shri.Binoy K. Ravindran. The very fact of realization of Rs. 96.00 lacs from the proceeds of the property mortgaged negates the allegation that the collateral security was not sufficient ab- initio to cover Bank's exposure. It is also established through investigation by Inspection Department that the firm M/s Karma Construction was in existence at the time of sanction of credit facilities and even thereafter and carrying on contract work for M/s FIT Ltd. (a Government of Kerala Undertaking) and Kerala Public Works Department. However it is also observed that there are a number of procedural lapses and negligence in handling the advance as brought out in Regular Inspection and subsequent investigation namely:

(i) Non-verification of end-use of funds resulting in diversion for purposes not related to business like payment to HDFC Bank for car and for apparent settlement of personal debts.

(ii) Absence of periodical verification of stocks in violation of guidelines and RO stipulation with only one godown Inspection report on record.

(iii) Improper monitoring of the account and allowing continuous overdrafts.

(iv) Non registration of P.O.A with firms whose receivables were financed.

(v) Failure to obtain C.A. certificate for receivables. (vi) Sanction of Open Cash Credit instead of Miscellaneous Cash Credit normally done for contractors (though Regional Office had approved the limit in pre-scrutiny).

(vii) Collateral Security was found to be 38.4 cents and not 40 cents of Land.

For the procedural lapses committed by all the three officials, Regular Departmental Action needs to be initiated. Under the circumstances, I am of the view that ends of justice will be met by conducting Departmental Action against the three officials namely Shri. C. K. Sathyanathan, Shri. K. V. Jaine and Shri. N. Suresh and there is no need to give sanction for prosecution by CBI unless any new facts come to light. CBI may be informed accordingly."

Accordingly, that order has been communicated to the CBI. Thereafter, the Superintendent of Police, CBI, Cochin, by his letter dated 13/15-10-2009 requested to review the order dated 24-09-2009 passed by the second respondent and to grant sanction for prosecution. In the letter so sent by the Superintendent of Police reiterates the allegations against the petitioners and others as detailed in the report originally sent by him to the Bank. The letter sent by the CBI for reviewing the earlier order passed by the second respondent on 24-09-2009 was not after conducting any further investigation into the matter. The Superintendent of Police does not have a case in the letter dated 13/15-10-2009 that a further investigation has been conducted into the allegations against the petitioners and others and based on the further materials so collected, the letter for reviewing the order dated 24-09-2009 has been sent to the Bank. The records clearly indicate that the letter dated 13/15-10-2009 has been sent by the Superintendent of Police to the Bank without collecting any further materials by way of conducting further investigation into the allegations against the petitioners and others.

14. The second respondent, after receiving the letter dated 13/15-10-2009 from the Superintendent of Police, issued Ext.P1 order dated 26-10-2009 granting sanction for prosecution of the petitioners and another. Ext.P1 order does not say that it is issued reviewing the earlier order passed on 24-09-2009. The letter dated 13/15-10-2009 sent by the Superintendent of Police does not find a reference in it. The earlier order dated 24-09-2009 passed by the second respondent contains a stipulation that there was no need to give sanction for prosecution by CBI unless any new facts come to light. Ext.P1 does not say that any new fact so came to light. In short, no reason is discernible from Ext.P1 as to why it was passed by the second respondent after declining sanction by order dated 24-09-2009. The materials supplied by CBI and available before the second respondent while passing order dated 24-09-2009 and the materials available before him while passing Ext.P1 order were the same. No different or further materials were made available by the CBI to the second respondent for his consideration while passing Ext.P1 order of sanction. Curiously enough, the second respondent has not stated any reason at all in Ext.P1 for deviating from the order passed by him on 24-09-2009 declining sanction for prosecution. Therefore, the same set of facts and allegations weighed with the second respondent initially for declining sanction and subsequently for granting sanction for prosecution.

15. I shall now consider the matter in the light of judicial pronouncements. Learned Standing Counsel for the first respondent contended, relying on the decision rendered by the Honourable Supreme Court in

Parmanand Dass v. State of A. P. [(1978) 4 SCC 32]

that there could be no legal bar to the sanctioning authority revising its own opinion before the sanction order is placed before the court. The relevant portion of the judgment relied on reads as follows:

"4. It was submitted that having once declined to grant sanction, a subsequent Standing Committee cannot grant sanction on the same facts. It was contended that the grant of sanction by the Special Officer was not bona fide and was due to ulterior motive. We do not see any merit in any of these submissions. Sanction given by the Commissioner was rightly rejected by the Special Judge on the ground that the Commissioner was not competent to grant the sanction. This could not prevent a subsequent sanction being given by the Competent Authority, but the plea of the learned Counsel was that the Standing Committee again considered the question but decided to drop the proceedings on the ground that it was an old case and the accused had already been reinstated in service. There could be no objection to the Standing Committee again reconsidering its decision. The validity of the sanction can only be considered at the time when it is filed before the Special Judge. We find that there could be no legal-bar to the sanctioning authority revising its own opinion before the sanction order is placed before the Court."

The said finding was entered by the Honourable Supreme Court in the premise of the peculiar facts obtained in that case. It was not a case where the sanctioning authority initially declined sanction as happened in the case on hand.

16. Learned Standing Counsel further contended, relying on the decision in

Surat Ram Sharma v. State of Punjab (2011 Crl. L. J. 3060)

that an earlier order passed by the competent authority declining sanction for prosecution can be reviewed when irrelevant consideration has been taken into account in the earlier order and relevant consideration has been ignored. That decision has been rendered by a Division Bench of the Punjab and Haryana High Court. In that case, even though no fresh materials were furnished to the Government, sanction was accorded by taking into account the whole investigation file. Even though that file was presented to the sanctioning authority earlier, that was not considered while passing the earlier order declining sanction. Therefore, it was found therein that the power of review can be exercised when irrelevant consideration has been taken into account in the earlier order and relevant consideration has been ignored as happened in that case. In the case on hand, the question is different. The second respondent does not have a case in Ext.P1 that certain relevant considerations had been ignored while he was passing the order declining sanction and taking into account such relevant considerations he has reviewed his earlier order and granted sanction for prosecution by Ext.P1 order. Moreover, the respondents could not successfully point out any such relevant considerations ignored by the second respondent while passing the earlier order and such considerations weighed with the second respondent while issuing Ext.P1 order. Therefore, Surat Ram Sharma (supra) cannot be gainfully used by the first respondent as a support for Ext.P1.

17. The Punjab and Haryana High Court, in the aforesaid decision, referred to the decision rendered by the Honourable Supreme Court in

State of Punjab v. Mohd. Iqbal Bhatti [(2009) 17 SCC 92]

The Honourable Supreme Court has held in that decision as follows:

"6. Although the State in the matter of grant or refusal to grant sanction exercises statutory jurisdiction, the same, however, would not mean that power once exercised cannot be exercised once again. For exercising its jurisdiction at a subsequent stage, express power of review in the State may not be necessary as even such a power is administrative in character. It is, however, beyond any cavil that while passing an order for grant of sanction, serious application of mind on the part of the authority concerned is imperative. The legality and/or validity of the order granting sanction would be subject to review by the criminal courts. An order refusing to grant sanction may attract judicial review by the superior courts." It was also observed by the Supreme Court in paragraph 21 of the same judgment as follows: "The High Court in its judgment has clearly held, upon perusing the entire records, that no fresh material was produced. There is also nothing to show as to why reconsideration became necessary. On what premise such a procedure was adopted is not known. Application of mind is also absent to show the necessity for reconsideration or review of the earlier order on the basis of the materials placed before the sanctioning authority or otherwise."

The matters observed by the Honourable Supreme Court in the said paragraph 21 apply squarely to the case on hand. There is nothing to show as to why reconsideration became necessary. On what premise such a procedure was adopted by the second respondent is not known. Application of mind is also absent to show the necessity for reconsideration or review of the earlier order on the basis of the materials placed before the sanctioning authority or otherwise.

18. The Honourable Supreme Court in

State of H.P. v. Nishant Sareen [(2010) 14 SCC 527]

has considered a case where the Principal Secretary, Health, Government of Himachal Pradesh, is the competent authority for according sanction. The Principal Secretary, on examining the case on the basis of the materials placed before her, found no justification in granting sanction to prosecute the accused. Therefore, sanction was refused. Thereafter, the Vigilance Department took up the matter again with the Principal Secretary for grant of sanction as in their opinion sufficient evidence existed to prosecute the accused. Thereafter, in the absence of any further materials, the Principal Secretary reconsidered the matter and granted sanction to prosecute the accused. On considering the matter in the light of judicial precedents, the Honourable Supreme Court has held in that case as follows:

"12. It is true that the Government in the matter of grant or refusal to grant sanction exercises statutory power and that would not mean that power once exercised cannot be exercised again or at a subsequent stage in the absence of express power of review in no circumstance whatsoever. The power of review, however, is not unbridled or unrestricted. It seems to us a sound principle to follow that once the statutory power under Section 19 of the 1988 Act or Section 197 of the Code has been exercised by the Government or the competent authority, as the case may be, it is not permissible for the sanctioning authority to review or reconsider the matter on the same materials again. It is so because unrestricted power of review may not bring finality to such exercise and on change of the Government or change of the person authorised to exercise power of sanction, the matter concerning sanction may be reopened by such authority for the reasons best known to it and a different order may be passed. The opinion on the same materials, thus, may keep on changing and there may not be any end to such statutory exercise."

In the case on hand, the second respondent issued an order on 24-09-2009 declining sanction for prosecution. Thereafter, based on the same set of materials, granted sanction for prosecution by issuing Ext.P1 order. The Honourable Supreme Court again observed in Nishant Sareen (supra) as follows:

"13. In our opinion, a change of opinion per se on the same materials cannot be a ground for reviewing or reconsidering the earlier order refusing to grant sanction. However, in a case where fresh materials have been collected by the investigating agency subsequent to the earlier order and placed before the sanctioning authority and on that basis, the matter is reconsidered by the sanctioning authority and in light of the fresh materials an opinion is formed that sanction to prosecute the public servant may be granted, there may not be any impediment to adopt such a course."

The CBI does not have a case that they have collected fresh materials subsequent to the earlier order and placed before the second respondent and on that basis the matter was reconsidered by him in the light of the fresh materials. The second respondent also does not have such a case in Ext.P1 order. Moreover, the letter dated 13/15-10-2009 sent by the CBI to the Bank for reviewing the earlier order does not supply any such fresh materials collected for the second respondent to reconsider or review the matter.

19. The respondents 2 to 4, in their counter affidavit, contended as follows:

".......... The second respondent on careful examination of the new facts, circumstances brought out by the Central Bureau of Investigation, with due application of mind, came to the conclusion that Sri.C.K.Sathianathan, Sri.N.Suresh and Sri.K.V.Jaine abused their position as public servants and entered into a criminal conspiracy to confer undue pecuniary advantage to Sri.Binoy K Ravindran without any public interest and thereby cheated the Bank, rendering them liable for offences punishable under Section 120-B read with Section 420 IPC and Section 13(2) read with Section 13(1)(d) of the Prevention of Corruption Act 1988 and accordingly granted sanction to the Central Bureau of Investigation under Section 19 of the Prevention of Corruption Act as per Exhibit P1 Sanction Order. .........."

The contention so raised appears to be an afterthought. This cannot be accepted. The second respondent does not say in Ext.P1 that he had examined any new facts or circumstances brought to his notice by the CBI and applied his mind to those facts or circumstances for the purpose of coming to the conclusion that the petitioners and another abused their position as public servants and committed the offences alleged and hence granted sanction for their prosecution. The Honourable Spreme Court in

Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commr. [(1978) 1 SCC 405]

has held as follows:

"8. The second equally relevant matter is that when a statutory functionary makes an order based on certain grounds, its validity must be judged by the reasons so mentioned and cannot be supplemented by fresh reasons in the shape of affidavit or otherwise. Otherwise, an order bad in the beginning may, by the time it comes to Court on account of a challenge, get validated by additional grounds later brought out. We may here draw attention to the observations of Bose, J. in Commr. of Police, Bombay v. Gordhandas Bhanji (AIR 1952 SC 16): Public orders, publicly made, in exercise of a statutory authority cannot be construed in the light of explanations subsequently given by the officer making the order of what he meant, or of what was in his mind, or what he intended to do. Public orders made by public authorities are meant to have public effect and are intended to affect the actings and conduct of those to whom they are addressed and must be construed objectively with reference to the language used in the order itself. Orders are not like old wine becoming better as they grow older."

The law thus declared was followed by the Honourable Supreme Court in Rashmi Metaliks Ltd. v. Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority [(2013) 10 SCC 95]. The principles thus enunciated are squarely applicable to the case on hand. The respondents cannot be permitted to justify Ext.P1 order by showing some reasons explained at a later point of time in their counter affidavit filed before the court. The justification, if any, for issuing Ext.P1 order by the second respondent should find a place in Ext.P1 itself. The justification, as contended in his counter affidavit, cannot make Ext.P1 valid.

20. The second respondent has declined to grant sanction for prosecution of the petitioners and another by his order dated 24-09-2009. The Honourable Supreme Court in Nishant Sareen (supra) has observed as follows:

"15. By way of footnote, we may observe that the investigating agency might have had legitimate grievance about the Order dated 27-11-2007 refusing to grant sanction, and if that were so and no fresh materials were necessary, it ought to have challenged the order of the sanctioning authority but that was not done. The power of the sanctioning authority being not of continuing character could have been exercised only once on the same materials."

The CBI has not chosen to challenge the order passed by the second respondent declining sanction.

21. In the case on hand, the loanee has settled the account by repaying the amount. Learned Standing Counsel for the first respondent submitted that the fact that the amount was repaid is no ground for denying sanction for prosecution. He has relied on the decision in

CBI. v. Jagjit Singh [(2013) 10 SCC 686]

in order to support that contention. In that decision, the Honourable Supreme Court was dealing with a case where the criminal proceedings against the loanee could be set aside by the High Court in the facts and circumstances of that case. It was not a case where sanction for prosecution was initially declined and subsequently, without any further materials, granted by the sanctioning authority. Therefore, that decision cannot be applied in this case. Similarly, the rulings in

Gokulchand Dwarkadas v. The King (A.I.R. (35) 1948 Privy Council 82)

Biswabhusan v. State of Orissa (A.I.R. 1954 S. C. 359)

and

State of Maharashtra v. Mahesh G. Jain [(2013) 8 SCC 119]

cited by the learned Standing Counsel also do not apply to the facts and the questions involved in the case on hand.

22. The learned Standing Counsel submitted that the CBI has filed the Final Report in the case along with Ext.P1 order of sanction issued by the second respondent and the Special Court has taken cognizance of the offences alleged against the petitioners and another. Therefore, he contended, relying on the decisions in

Dinesh Kumar v. Chairman, Airport Authority of India (AIR 2012 SCC 858)

CBI v. Ashok Kumar Aggarwal (AIR 2014 SC 827)

and

State of Bihar v. Rajmangal Ram (AIR 2014 SC 1674)

that this Court cannot interfere with the order of sanction and, in turn, the criminal proceedings pending at this stage. Dinesh Kumar (supra) is a case where the sanction order was challenged before the High Court. The High Court, observing that it was open to the accused to question the validity of the sanction order during trial on all possible grounds and the CBI could also justify the order granting sanction before the trial judge, dismissed the writ petition of the accused. The Honourable Supreme Court upheld the decision of the High Court. In the judgment, the Honourable Supreme Court referred to the ruling in

Parkash Singh Badal v. State of Punjab (AIR 2007 SC 1274)

In that ruling, the Honourable Supreme Court observed as follows:

"53. The sanction in the instant case related to offences relatable to Act. There is a distinction between the absence of sanction and the alleged invalidity on account of non application of mind. The former question can be agitated at the threshold but the latter is a question which has to be raised during trial."

The difference between Dinesh Kumar (supra) and the case on hand is that there was no declining of sanction at the first instance in the former case, but there was declining of the same at the first instance in the latter case. In other words, sanction was granted at the first instance in the former case and sanction was denied at the first instance in the latter case. While dealing with such a case, the Honourable Supreme Court has held as follows:

"13. In our view, having regard to the facts of the present case, now since cognizance has already been taken against the appellant by the Trial Judge, the High Court cannot be said to have erred in leaving the question of validity of sanction open for consideration by the Trial Court and giving liberty to the appellant to raise the issue concerning validity of sanction order in the course of trial. Such course is in accord with the decision of this Court in Parkash Singh Badal and not unjustified."

Therefore, the decision in Dinesh Kumar (supra) cannot be applied in the case on hand. This is a case where no sanction was originally granted and Ext.P1 under challenge is unsustainable in the light of the law already discussed.

23. Ashok Kumar Aggarwal (supra) is a case where the Special Judge rejected the application of the accused questioning the sanction granted by the competent authority under Section 19 of the PC Act observing that the issue could be examined during trial. In the revision application preferred by the accused, the High Court set aide the order of the Special Judge and remanded the case to record a finding on the question of any failure of justice in according sanction and examining the sanctioning authority as a witness even at pre-charge stage if deems fit. The appeal preferred by the CBI before the Supreme Court has been dismissed. The Honourable Supreme Court referred to Parkash Singh Badal (supra) and Dinesh Kumar (supra) in the judgment. It is quite evident that the questions dealt with in Ashok Kumar Aggarwal (supra) and the questions involved in the case on hand are different in nature. Therefore, this decision also cannot be accepted as an authority for finding that the remedy of the petitioners is before the trial court.

24. In Rajmangal Ram (supra), the Honourable Supreme Court was considering the question of law as to "whether a criminal prosecution ought to be interfered with by the High Courts at the instance of an accused who seeks mid-course relief from the criminal charges levelled against him on grounds of defects, omissions or errors in the order granting sanction to prosecute including errors of jurisdiction to grant such sanction?". It was a case where two appeals filed by the State against separate orders passed by the High Court, the effect of which was that the criminal proceedings instituted against the respondents under different provisions of the IPC as well as the PF Act have been interdicted on the ground that sanction for prosecution of the respondents in both the cases has been granted by the Law Department of the State and not by the parent department to which the respondents belong. Therefore, the questions dealt with by the Honourable Supreme Court in this case are different from the questions involved in the case on hand. In other words, it was not a case where the competent authority initially refused to grant sanction as in the case on hand and granted sanction subsequently at the instance of CBI without adverting to any special reason for doing so. Therefore, in the peculiar facts and circumstances of this case, the decisions relied on by the learned Standing Counsel will not persuade this Court to dismiss this writ petition relegating the petitioners to take up the question of validity of Ext.P1 before the trial court.

25. The Honourable Supreme Court in

Anil Kumar v. Aiyappa [2013 (4) KLT 125 (SC)]

considered the question whether the Special Judge/Magistrate was justified in referring a private complaint made under Section 200 of Cr.P.C for investigation by the Deputy Superintendent of Police, Karnataka Lokayukta, in exercise of powers conferred under Section 156(3) of Cr.P.C without the production of a valid sanction order under Section 19 of the PC Act. The Honourable Supreme Court, relying on the decisions in

State of Uttar Pradesh v. Paras Nath Singh [(2009) 6 SCC 372)]

and in

Subramanium Swamy v. Manmohan Singh & Anr. [(2012) 3 SCC 64]

has held as follows:

"13. Learned senior counsel appearing for the appellants raised the contention that the requirement of sanction is only procedural in nature and hence, directory or else S.19(3) would be rendered otiose. We find it difficult to accept that contention. Sub-section (3) of S.19 has an object to achieve, which applies in circumstances where a Special Judge has already rendered a finding, sentence or order. In such an event, it shall not be reversed or altered by a court in appeal, confirmation or revision on the ground of absence of sanction. That does not mean that the requirement to obtain sanction is not a mandatory requirement. Once it is noticed that there was no previous sanction, as already indicated in various judgments referred to hereinabove, the Magistrate cannot order investigation against a public servant while invoking powers under S.156(3) Cr.P.C. The above legal position, as already indicated, has been clearly spelt out in Paras Nath Singh and Subramanium Swamy cases (supra)."

Thus, the Honourable Supreme Court has held in this ruling that even at a pre-cognizance stage, the sanction was necessary. Moreover, a judgment rendered by the Honourable Supreme Court in Crl. Appeal No.257 of 2011 in General Officer, Commanding v. C.B.I. has been referred to in this judgment. The relevant paragraph of the judgment quoted in Anil Kumar (supra) reads as follows:

"Thus, in view of the above, the law on the issue of sanction can be summarized to the effect that the question of sanction is of paramount importance for protecting a public servant who has acted in good faith while performing his duty. In order that the public servant may not be unnecessarily harassed on a complaint of an unscrupulous person, it is obligatory on the part of the executive authority to protect him....... If the law requires sanction, and the court proceeds against a public servant without sanction, the public servant has a right to raise the issue of jurisdiction as the entire action may be rendered void ab-initio."

These two rulings of the Honourable Supreme Court, in unequivocal terms, show that a sanction order under Section 19 is necessary for proceeding against the petitioners. The sanction order means a valid sanction order. The facts narrated and the rulings considered in this judgment would show that Ext.P1 sanction order was passed in an illegal manner. Therefore, Ext.P1 cannot sustain in the eye of law. In that view of the matter, there is nothing wrong on the part of this Court to entertain and consider this writ petition filed by the petitioners challenging the validity of Ext.P1 sanction order without relegating them to challenge the same before the trial court. Section 19(1) of the PC Act, 1988 reads as follows:

(1) No court shall take cognizance of an offence punishable under sections 7, 10, 11, 13 and 15 alleged to have been committed by a public servant, except with the previous sanction,--

(a) in the case of a person who is employed in connection with the affairs of the Union and is not removable from his office save by or with the sanction of the Central Government, of that Government;

(b) in the case of a person who is employed in connection with the affairs of a State and is not removable from his office save by or with the sanction of the State Government, of that Government;

(c) in the case of any other person, of the authority competent to remove him from his office."

Thus, Section 19(1) prescribes three categories of authorities competent to grant previous sanction for taking cognizance of the offences named therein committed by a public servant. An authority exercising powers under this Section shall exercise the same independently and objectively. The grant of sanction is an important and sacrosanct act to be performed by a competent authority. The legislature thought it fit to confer power on the authority competent to remove a public servant from his office for granting such a sanction. The conferment of power on such authority is with certain objectives. That authority will be able, in the facts and circumstances of each case, to ascertain whether an offence committed by the public servant warrants criminal prosecution or not. Similarly, such authority is the most appropriate authority to judge as to whether the allegations are frivolous or speculative. That authority is in a better position to assess and understand the nature of work being carried on by that person and what are the attendant facts and circumstances involved in relation to the allegations against that person. The mere fact that the evidence collected by the prosecuting agency discloses a prima facie case against the person sought to be prosecuted ipso facto is no ground for granting sanction. On considering various relevant facts and circumstances concerning that person as also concerning the allegations levelled against him, the competent authority for granting sanction has to take a decision whether sanction is to be granted or not.

26. The sanctioning authority can refuse sanction, even in a case where an offence is made out prima facie against a public servant, for various reasons. As held by the Honourable Supreme Court in Gokulchand Dwarkadas (supra), even political or economic grounds can be weighed with the competent authority to consider a prosecution as inexpedient. The competent authority alone would be a real judge to consider whether, in the alleged facts and circumstances, there was a real abuse or misuse of office held by the public servant. That authority really knows the nature of the functions discharged by the public servant and whether he has abused or misused the same. In order to consider all the necessary facts and circumstances while granting or not granting sanction for prosecution, the legislature purposely granted such power on an authority competent to remove a public servant from his office. These principles are to be weighed with the sanctioning authority while considering the question of granting or not granting sanction for prosecution. The relevant principles so found are also emerging from the ruling of the Honourable Supreme Court in

R.S. Nayak v. A.R.Antulay [(1984) 2 SCC 183]

27. In the case on hand, the second respondent has considered the report of the CBI as well as the note of the Vigilance Department of the Bank. After adverting to the relevant facts, that authority found that departmental proceedings against the petitioners and another would be sufficient and there was no need for any criminal prosecution unless new facts come to light. The CBI has registered the case against the petitioners and another not based on any complaint preferred by the Bank. But, according to them, it was based on some source information. What was that source of information is not in evidence. Be that as it may. The second respondent, after considering the attendant facts and circumstances, independently arrived at a conclusion that no sanction need be granted for prosecution and departmental proceedings alone would be sufficient. Such a finding has been entered by the second respondent independently while considering the report of the CBI and the connected records. The report of the CBI and the connected records prima facie show the commission of offences alleged. Even after considering those aspects, the second respondent arrived at the conclusion in his order passed on 24-09-1999. Testing that conclusion arrived at by the second respondent in the light of different judicial pronouncements, this Court does not find any illegality in it.

28. The CBI, thereafter, again approached with their request for reviewing the earlier order passed by the second respondent refusing sanction for prosecution. Soon after the receipt of such a request for review from the CBI, absolutely without assigning any reason whatsoever, the second respondent granted Ext.P1 order sanctioning prosecution of the petitioners and another. The second respondent, in Ext.P1, does not even say that he was reviewing his earlier order. Ext.P1 is keeping mum as to what are the materials subsequently weighed with the second respondent for granting sanction. Ext.P1 is presented as if it is originally passed by the second respondent in the matter. It is astonishing to note that the second respondent passed an order like Ext.P1 without even referring to the earlier order passed by him and without even mentioning any reason that prompted him to pass such an order. These facts assume significance in the light of the argument advanced by the learned Senior Counsel for the petitioners that the second respondent was compelled to pass such an order based on the pressure exerted by the CBI. The statement filed by the CBI in this Court in a cryptic way without disclosing the true facts is also supplementing to that significance. The second respondent independently considered the matter originally and decided not to grant sanction for the reasons stated by him. No reason is stated in Ext.P1 order that prompted the second respondent to deviate from his earlier stand declining sanction. There happened only one thing in between. That is the letter dated 13/15-10-1999 sent by the CBI requesting for reviewing the earlier order passed by the second respondent. When all these facts are considered in their right perspective, it can reasonably be found that the second respondent has passed Ext.P1 order granting sanction for prosecution only at the instance of and due to the compulsion by the CBI as contended by the learned Senior Counsel.

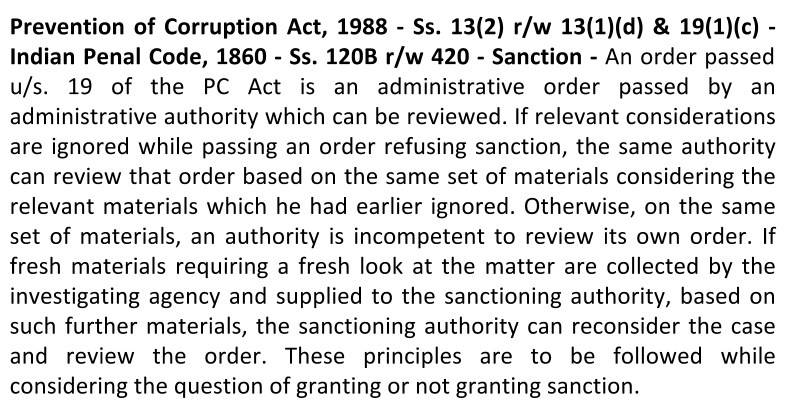

29. In the light of the judicial pronouncements in respect of the power of review of an order passed under Section 19 of the PC Act, the principles enunciated can be summed up as follows:

30. An order passed under Section 19 of the PC Act is an administrative order passed by an administrative authority which can be reviewed. If relevant considerations are ignored while passing an order refusing sanction, the same authority can review that order based on the same set of materials considering the relevant materials which he had earlier ignored. Otherwise, on the same set of materials, an authority is incompetent to review its own order. If fresh materials requiring a fresh look at the matter are collected by the investigating agency and supplied to the sanctioning authority, based on such further materials, the sanctioning authority can reconsider the case and review the order. These principles are to be followed while considering the question of granting or not granting sanction.

31. In the case on hand, the second respondent has passed Ext.P1 order not based on any fresh materials, but based on the very same materials which were available with him while refusing to grant sanction by his order dated 24-09-1999. This is illegal and hence unsustainable in law.

32. For the foregoing reasons and discussions, Ext.P1 order passed by the second respondent granting sanction for prosecuting the petitioners is illegal and liable to be quashed.

In the result, Ext.P1 is quashed.

This writ petition is allowed as above.