(2015) 391 KLW 901

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM

PRESENT: THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.HARIPRASAD

WEDNESDAY, THE 28TH DAY OF JANUARY 2015/8TH MAGHA, 1936

RSA.No. 14 of 2015

AGAINST THE JUDGMENT IN A.S.NO. 157/2014 of SUB COURT, CHAVAKKAD DATED 27-09-2014 AGAINST THE JUDGMENT IN O.S.NO. 634/2004 of MUNSIFF COURT,CHAVAKKAD DATED 09-06-2010

APPELLANT(S)/APPELLANTS/DEFENDANTS

GIRIJA AND ORS.

BY ADV. SRI.RAJIT

RESPONDENT(S)/RESPONDENTS/PLAINTIFFS

RAJAN AND ANR.

JUDGMENT

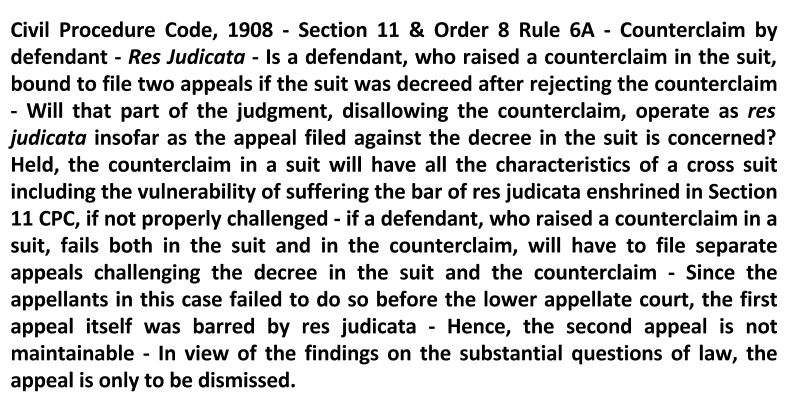

The substantial questions of law arising in this second appeal are thus:

Is a defendant, who raised a counter claim in the suit, bound to file two appeals if the suit was decreed after rejecting the counter claim?

Will that part of the judgment, disallowing the counter claim, operate as res judicata insofar as the appeal filed against the decree in the suit is concerned?

2. Factual matrix, in the shortest form, is thus:

Appellants were defendants in a suit for permanent prohibitory injunction filed by the respondents alleging that they were trying to trespass into the plaint schedule property over which the respondents have exclusive title and possession. In the suit, the appellants filed a written statement raising a counter claim under

Order 8 Rule 6A of the Code of Civil Procedure

(in short, "CPC"). The appellants not only denied the allegations in the plaint that they attempted to trespass into the property, but also raised a contention that the respondents were trying to annihilate their right of way over the plaint schedule property. The trial court decreed the suit and dismissed the counter claim. The appellants took up the matter in first appeal to the lower appellate court. After re-appreciating the evidence, the lower appellate court dismissed the appeal confirming the decree of the trial court. It is pertinent to note that only one appeal was filed by the appellant challenging the decree in the suit as well as that in the counter claim.

3. Feeling aggrieved by dismissal of the appeal, the appellants have preferred this second appeal. At the time of hearing on admission, the above questions were raised.

4. Heard Shri Rajit, the learned counsel for the appellants elaborately. I have perused the records.

5. Learned counsel for the appellants contended that the suit and the counter claim should be regarded as a single/unified proceedings. It is also contended that there is no necessity to file two separate appeals challenging the adverse decisions in the suit and the counter claim. Some precedents were also cited at the Bar. Before dealing with the decisions cited, I shall deal with the statutory provisions.

Order 8 Rule 6A CPC reads as follows:

(1) A defendant in a suit may, in addition to his right of pleading a set-off under rule 6, set up, by way of counter-claim against the claim of the plaintiff, any right or claim in respect of a cause of action accruing to the defendant against the plaintiff either before or after the filing of the suit but before the defendant has delivered his defence or before the time limited for delivering his defence has expired, whether such counter-claim is in the nature of a claim for damages or not :

Provided that such counter-claim shall not exceed the pecuniary limits of the jurisdiction of the Court.

(2) Such counter-claim shall have the same effect as a cross-suit so as to enable the Court to pronounce a final judgment in the same suit, both on the original claim and on the counter-claim.

(3) The plaintiff shall be at liberty to file a written statement in answer to the counter-claim of the defendant within such period as may be fixed by the Court.

(4) The counter-claim shall be treated as a plaint and governed by the rules applicable to plaints."

On a careful reading of the above provision, it can be seen that a defendant in a suit is permitted by law to resist the action and, still further, to raise a counter claim against the claim of the plaintiff. In this context, it is apposite to note that Order 8 Rule 6 CPC empowers a defendant to raise a claim of set-off against the plaintiff's claim in a suit for recovery of money. It is indisputable that the counter claim by the defendant need not be confined to monetary claims alone. It can be for any relief, subject to the condition that the claim shall be in respect of any right arising from a cause of action accrued to the defendant against the plaintiff either before or after filing of the suit, but before the defendant has delivered his defence or before the time limited for delivering his defence was expired. Another restriction is that the counter claim shall not exceed the pecuniary limits of jurisdiction of the court in which the suit is laid. Sub-rule (2) of Order 8 Rule 6A CPC specifically says that such a counter claim shall have the same effect as a cross suit so as to enable the court to pronounce a final judgment in the same suit, both on the original claim and on the counter claim. Instead of filing a cross suit, the Code itself allows a defendant to raise a counter claim, which should be tried as a single suit, though in reality they are cross suits. Sub-rule (3) of the said provision makes it clear that the plaintiff shall be at liberty to file a written statement in answer to the counter claim raised by the defendant. It is obvious that if the plaintiff fails to file a written statement to the counter claim, the consequence envisaged under Order 8 Rule 10 CPC will be the result. Sub-rule (4) shows that the counter claim shall be treated as a plaint and governed by the rules applicable to the plaints. The above provisions would show that a counter claim raised by a defendant in a suit is essentially a separate suit having all the characteristics of a cross suit, including the necessity of paying court fee. True, taking out summons to the opposite party, etc. may not be necessary.

6. Order 8 Rule 6C CPC empowers the plaintiff to raise a contention that the counter claim raised by the defendant in his suit may be excluded, provided he makes an application at any time before the issues are settled in relation to the counter claim. And the court, on a hearing such application, shall pass appropriate orders. The apparent idea behind this provision is to avoid frustration or embarrassment of trial of the suit. Order 8 Rule 6D CPC spells out that in any case in which the defendant has set up a counter claim, the staying, discontinuance or dismissal of the suit will not affect the counter claim and it can be proceeded with. These provisions reinforce the principle that a counter claim is a cross suit with all the trappings of a separate suit.

7. There was a conflict of decisions on the point if two suits involving common issues were disposed of in one judgment and an appeal was filed against the decree in one and not in the other, the matter decided in the latter suit becomes res judicata so that it cannot be reopened in appeal. However, it is now well settled that where an appeal arising out of a connected suit is dismissed on merit, the other appeal in respect of the other suit cannot be heard and has to be dismissed as the second one is barred by res judicata. Similarly, where no separate appeals are filed from the decrees in the connected suits, it is now settled that it has the same effect of non-filing appeal against a judgment and decree resulting in the bar of res judicata. If the findings recorded in one of the connected suits are allowed to reach finality, the appellate court is precluded from proceeding with the appeal against the decree in the other suit.

There is a large body of case law to support this proposition. It will be useful to mention a couple of decisions to strengthen this reasoning. The law on the point is succinctly stated in a Full Bench decision of this Court in

Janardhanan Pillai and others v. Kochunarayani Amma and others (ILR 1976 (1) Kerala 489)

The following quotation is relevant for our purpose:

"It is the decree which is the foundation for the appeal. The scheme of the Code of Civil Procedure is to provide for a decree and judgment in every suit. The fact that the court orders joint trial of two suits in exercise of its inherent power does not mean that it dispenses with the passing of judgment and decree in the suit as required by the Civil Procedure Code. Consolidation of two suits need not necessarily be by agreement of parties, for, if a court, after hearing parties, feels that, in the interests of justice, it is necessary that two or more proceedings should be tried together, it is open to it to order so to avoid repetition of the same evidence in the different cases or to avoid the possibility of conflicting decisions in those cases or for such other justifying reasons. But nevertheless the court is not absolved from the duty of passing a judgment in those cases nor drawing up decrees in those cases. May be that a common judgment is delivered by a court but it is, in essence, a judgment in each and everyone of the cases and decrees have to be drawn up in those different cases. May be that there is only one trial. But that, does not in any way affect the rule that there should be separate appeals. If the consequence of a decree being left unchallenged is to render it final, such consequence will work itself out irrespective of the question whether the decree in the connected suit has been subjected to appeal. When a party has obtained the benefit of the finality of a decision in one suit if proceeding by way of appeal in a connected suit is nevertheless to continue, necessarily the party has to face the same issue twice over. It is not possible to find any logic which compels us to adopt the view that an earlier decision in a former suit may not operate as res judicata in the event that decision was reached simultaneously with the decision in the suit from which the appeal is taken. That would be against the plain provision in section 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The question whether the plea of res judicata is available is to be decided with reference to the time the matter comes up for consideration and if by that time there is an earlier decision by a competent court between the same parties which has become final and the question is directly and substantially the same such earlier decision would operate as res judicata barring a fresh decision by the appellate court."

The Apex Court in

Premier Tyres Ltd. v. Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (1993(2) KLT 130)

considered the question and held thus:

"Where an appeal arising out of connected suit is dismissed on merits the other cannot be heard, and has to be dismissed. Where no appeal is filed, as in this case from the decree in connected suit it has the same effect of non filing of appeal against a judgment or decree. Thus the finality of finding recorded in the connected suit, due to non filing appeal precludes the Court from proceeding with appeal in other suit."

The above proposition of law is now unchallengeable in view of the subsequent line of binding decisions as well.

8. The principle of res judicata applies between two stages in the same litigation is also well settled. Where a trial court or a higher court has, at an earlier stage, decided the matter in one way, the parties cannot re-agitate the matter at a subsequent stage of the same proceeding.

The Supreme Court in

C. V. Rajendran and another v. N. M. Muhammed Kunhi (AIR 2003 SC 649)

held that the principle of res judicata applies as between two stages in the same litigation so that, if any issue has been decided at an earlier stage against the party, it cannot be re-agitated by him at a subsequent stage in the same suit or proceeding. Catena of decisions could be seen on this point and the said proposition is beyond any scope of challenge.

9. What is the impact of the said principles in a case wherein the suit is resisted by a defendant not only by denying the plaintiff's claim, but also by raising a counter claim?

Will the principle of res judicata come into play, if no appeal is filed against the decree in the counter claim?

Learned counsel for the appellants would contend that there is no need to file a separate appeal by the defendant in such a situation. According to the learned counsel, the decision of this Court in

Philip v. Kinhimohammed (2006 (4) KLT 998)

will fortify his line of argument. I have gone through the decision carefully. Learned Single Judge therein was considering the question as to where the first appeal had to be filed in a suit where the plaint claim exceeded the pecuniary jurisdiction of the District Court and the valuation in the counter claim was well within the pecuniary limits of the District Court. Obviously, the appeal challenging the decree in the suit could only be filed before the High Court. In such cases, situations may arise necessitating the filing of appeals in two different fora. The learned Single Judge relying on a decision rendered by the Madras High Court in

T.K.V.S. Vidyapoornachary Sons v. M.R.Krishnamachary (AIR 1983 Mad. 291)

held that the suit claim and the counter claim should be regarded as a single proceedings for the purpose of valuation. The following observations in the judgment will throw light on the reasoning adopted by the learned Single Judge:

"When the homogeneity of this amounts to a single proceeding or a unification of the proceeding then necessarily, when that matter is decided and it goes to the higher forums it is that single proceeding which is being challenged before the appropriate forums. There may be cases where the plaint is dismissed and counter-claim is allowed and the plaintiff need challenge only the counter claim. In such circumstances, it depends upon the valuation of the counter claim that may decide the jurisdiction. .....................:

10. In Philip's case (supra) a passing observation of a Full Bench of this Court in

A.Z.Mohammed Farooq v. State Government (1984 KLT 346)

was also noticed. The factual senario in A.Z.Mohammed Farooq's case was totally different from the case in hand. After analysing the provisions in Order 8 Rule 6A CPC relating to filing of counter claim, the Full Bench opined that it is possible to hold that the 'subject matter' of the suit would be the aggregate of the amounts claimed in the plaint and in the written statement by way of counter claim. It is explicitly mentioned in the decision that it was not necessary for deciding the cases before the Full Bench to express a definite view on that larger aspect. Therefore, it is evident that the observations made by the Full Bench of this Court were in the nature of an obiter dicta only. It is very relevant to note that the question of barring an appeal in such a situation by res judicata was not considered by the Full Bench. Learned Single Judge in Philip's case (supra) also did not consider the impact of res judicata in an appeal, when no appeal was filed against the relief denied in a counter claim. In those decisions, the question of res judicata remained sub silentio, as the matters were decided without noticing the impact of the said rule of estoppal. Therefore, the decisions in A.Z.Mohammed Farooq's and Philip's cases cannot be taken as precedents laying down the proposition that no appeal need be filed or rather one appeal is sufficient, if a party is adversely affected by the decisions in both the suit and the counter claim.

11. In another decision, viz.,

Thomas and others v. D.Sudha and others (2010 (4) KHC 575)

a learned Single Judge of this Court while handling a case in which both the suit and the counter claim were dismissed and thereafter the plaintiff filed an appeal and the defendant filed a cross objection, held that the counter claim being a cross suit, the defendant has no right to question the correctness of decision on the counter claim by way of a cross objection in the appeal preferred by the plaintiff. This decision, in spite of its variegated factual and legal questions, may be applied to strengthen the view that a regular appeal is the remedy for a party aggrieved by the dismissal of his counter claim. Another decision cited by Shri Rajit is rendered by a learned Judge of this Court in

Nherapoyil N.P.Moideen v. K.Narayanan Nair (AIR 1997 Kerala 318)

This Court found that non-payment of court fee in a counter claim bars the appellate court from considering the question involved in the counter claim. It was also found that in such a situation the rejection of counter claim becomes final. Learned Single Judge has only made an observation that the question of discharge of the amount, raised by the defendant, can be decided by the appellate court de hors rejection of the counter claim. Such a statement of law will not help the appellant to raise a contention that there need not be a separate appeal on the dismissal of a counter claim.

12. Upshot of the discussion is that the counter claim raised in a suit shall be treated as a cross suit as per statutory mandate. It has all the trappings of a regular suit, like paying the requisite court fee, filing a written statement, raising the relevant issues and deciding the issues on evidence. It is also clear that the suit and the counter claim shall be disposed of by a judgment, but a decree shall be drawn up in the counter claim too, although it may be a composite one with the decree in the suit. Well settled is the proposition of law that the rule of estoppal in the form of res judicata will be attracted at a subsequent stage in the same suit, if findings on some of the issues are allowed to attain finality. The ratio in the decisions in A.Z.Mohammed Farooq's and Philip's cases (supra) only indicate the forum where an appeal has to be filed considering the suit claim and counter claim as a unified proceedings. The said decisions do not lay down a proposition that no separate appeal need be filed, if a party is prejudicially affected by the adjudication in the suit as well as in the counter claim. The question of res judicata was not at all adverted to in those decisions. The ratio in the binding precedents in Janardhanan Pillai and Premier Tyres Ltd. and other cases clearly lay down that there should be separate appeals in cross suits; otherwise the appeal filed against one decree allowing the other decree, the one passed simultaneously with the challenged decree, to become final, then the appeal will be barred by res judicata. I am of the definite view that the same principle is applicable in the case of a decree passed in a counter claim also.

13. Learned counsel for the appellants contended that Order 41 Rule 33 CPC gives ample power to an appellate court to pass any decree and to make any order which ought to have been passed or made and to pass or make such further or other decree or order as the case may require. It is also argued that the provision enables the court to pass a correct decree in the appeal, although the respondents or parties may not have filed any appeal or objection. And where there have been decrees in cross suits, where two or more decrees were passed in one suit, the appellate court is bound to pass appropriate decree although appeal/appeals may not have been filed against such decrees. The question that falls for consideration is whether the powers of the appellate court under Order 41 Rule 33 CPC can be invoked against specific statutory provisions contained in the other parts of the same Code. The proposition that the law stated in Section 11 CPC is applicable not only to suits, but also to appeals is clear and unchallengeable. Section 11 CPC prohibits the court from trying any suit or issue in which the matter directly and substantially in issue has been directly and substantially in issue in a former suit between the parties or between the parties under whom they or any of them claimed, litigating under the same title. Further, Section 11 CPC speaks about the competency of the courts to try the suits as well. Still further, the first suit must have been decided on merits, ie, heard and finally decided by a competent court. The Section creates an absolute bar against the court from deciding the subsequent suit falling within the ambit of Section 11 CPC. The bar created by Section 11 CPC is non-negotiable or indefeasible. The object of Order 41 Rule 33 CPC is to empower the appellate court to do complete justice between the parties. It is trite that for exercising the power under the said rule the parties to the proceedings must be before the court and the question raised properly arises out of the judgment of the lower court. In that event, the appellate court shall consider any objection to any part of the order or decree and set it right. Ordinarily an appellate court must not vary or reverse a decree or order in favour of a party who has not preferred any appeal and this rule holds good notwithstanding the provisions in Order 41 Rule 33 CPC. The Supreme Court has clearly stated that the power under Order 41 Rule 33 CPC is discretionary. It has been held in

State of Punjab v. Bakshish Singh ((1998) 8 SCC 222)

that the appellate court cannot, in the garb of exercising power under Order 41 Rule 33 CPC, enlarge the scope of appeal. Power under Order 41 Rule 33 CPC cannot be invoked in contravention of the statutory prescriptions in Section 11 CPC. Therefore, I am not inclined to accept the argument of the learned counsel that the appellate court has power to grant a relief to a non-appealing defendant, who lost his counter claim. It is all the more important to note that the incurable legal bar set in against the appellant for not challenging the dismissal of the counter claim before the lower appellate court cannot be undone in the second appeal.

14. From the above discussion, it is discernible that the law stated in Order 8 Rule 6A CPC makes it abundantly clear that the counter claim in a suit will have all the characteristics of a cross suit including the vulnerability of suffering the bar of res judicata enshrined in Section 11 CPC, if not properly challenged. Therefore, I find that the questions of law arising in this case can only be decided against the appellants, finding that if a defendant, who raised a counter claim in a suit, fails both in the suit and in the counter claim, will have to file separate appeals challenging the decree in the suit and the counter claim. Since the appellants in this case failed to do so before the lower appellate court, I am of the view that the first appeal itself was barred by res judicata. Hence, the second appeal is not maintainable. In view of the findings on the substantial questions of law, the appeal is only to be dismissed.

In the result, the appeal is dismissed. No costs.

All pending interlocutory applications will stand dismissed.