(2014) 385 KLW 449

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM

PRESENT: THE HONOURABLE THE AG.CHIEF JUSTICE MR.ASHOK BHUSHAN THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE A.M.SHAFFIQUE THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.V.RAMAKRISHNA PILLAI THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.HARIPRASAD & THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.K.JAYASANKARAN NAMBIAR

THURSDAY, THE 11TH DAY OF DECEMBER 2014/20TH AGRAHAYANA, 1936

WA.No. 385 of 2011 ( ) IN WP(C).3446/2011

AGAINST THE ORDER/JUDGMENT IN WP(C) 3446/2011 of HIGH COURT OF KERALA DATED 11-02-2011

APPELLANT(S)/APPELLANTS/3RD PARTIES

1. M.C.RATHEESH, S/O. CHANDRAN, MUTHALAMCHIRA HOUSE, P.O.SOUTH KONDAZHY THRISSUR DISTRICT.

2. GIREESAN T.P., S/O. APPUKUTTAN, THRITHALAPENNARVEETTIL HOUSE, SANTHI BHAVAN ENKAKKAD P.O., WADAKKANCHERY, THRISSUR DISTRICT.

BY ADV. SRI.I.DINESH MENON

RESPONDENT(S)/RESPONDENTS/PETITIONER IN THE W.P.C.

1. THE SECRETARY, REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY, THRISSUR - 680 001.

2. SRI.P.N.UNNIKRISHNAN, PARAYIL HOUSE, MANALITHARA P.O., THRISSUR-680 589.

R BY SRI.P.DEEPAK R1 BY SPL.GOVERNMENT PLEADER SRI.C.S.MANILAL

JUDGMENT

Ashok Bhushan, Ag.CJ.

A three Judge Bench has made the reference by order dated 16.10.2014 doubting correctness of an earlier Full Bench judgment of this Court reported in

Binu Chacko v. R.T.A., Pathanamthitta (2006(2) KLT 172)

In the reference order the Full Bench has observed that in Binu Chacko's case (supra), the Full Bench has dilated regarding the scope of the phrase 'person aggrieved'. The matter was placed before the Full Bench by reference order dated 30.3.2011 by a Division Bench. The learned Division Bench, after noticing the ratio of the Full Bench judgment in Binu Chacko's case (supra) and a Division Bench judgment in

Girija Devi v. K.T.Mathew (1991(1) KLT 353)

which was relied on in Binu Chakco's case (supra), in paragraphs 6 to 10, has opined as follows:

"6. From time to time question arose whether the existing operators have any legal right to raise such objections. The question which actually fell for consideration of the Full Bench in Binu Chacho v. R.T.A., Pathanamthitta [2006(2) KLT 172] was whether an oder granting permit is a revisable order under Section 90 of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 at the instance of a business rival, i.e., an existing permit holder. In view of apparently inconsistent views taken by two Division Benches of this Court, the matter came to be referred to Full Bench and by the abovementioned judgment, the Full Bench held at paragraph 28 as follows:

"We are of the view that the existing operator cannot invoke the revisional jurisdiction on the sole ground that the grant of permit to the opposite party prejudicially affects his rights. It is not as though he can impeach each and every order of the RTA or STA alleging illegality or impropriety. He can challenge only those orders against which he can have a legal grievance. He cannot be a person aggrieved in respect of every action or decision of RTA or STA. There are grievances which would give rise to a cause of action exclusively for the passengers only or sometimes to a local authority and the like. If the existing operator is given the right to challenge the very grant of permit or renewal of permit on the ground that he is aggrieved by such grant, it will amount to resurrecting a right which he was entitled to avail only under the old Act. It will be illogical and irrational to interpret the expression "person aggrieved" in Section 90 of the Act in such a manner as to take away the right given to a new entrant at the pre-permit stage to have a permit under the Act without obstruction from those already in the business, the very moment he is granted or issued a permit. Under normal circumstances, grievance of the existing operator shall be confined to disputes relating to settlement of timings and cannot be entertained against the grant of permit or renewal of permit as such."

7. The Full Bench reached on such a conclusion on the basis of an earlier Division Bench judgment reported in Girija Devi v. K.T. Mathew [1991(1) KLT 353]. We may mention here that neither in the Full Bench decision nor in the abovementioned Division Bench decision, there is discussion either on the language of Rule 212 or interpretation of the said rule in the context of the scheme of the new Motor Vehicle Act, 1988. The Full Bench took note of the fact that in view of the decision in Mithilesh Garg v. Union of India [AIR 1992 SCC 443] there is a change of the legislative policy under the 1988 Act compared to its predecessor Act of 1939 and therefore came to the conclusion that the existing operator cannot object to the grant of the permit, but the existing operator can raise objection regarding settlement of timings. With utmost respect to the Full Bench, we are of the opinion that such a conclusion, to our mind, appears to be inconsistent with the other principle laid down by the Full Bench that the existing operator has no right to object to the grant of new permits.

8. The learned counsel for the appellants however, referred to proviso to Rule 212 (3) which reads as follows:

"Provided that the State or Regional Transport Authority shall not however vary the timings of a service without giving to the interested permit holders an opportunity to represent their case." 9. As already noticed by us earlier, neither the language of the said proviso nor the scheme of the rule was the subject matter of discussion either by the Full Bench or by the earlier Division Bench relied upon by the Full Bench.

10. Prima facie we are of the opinion that the language of the abovementioned proviso confers a right on an existing operator of a stage carriage for an opportunity to represent his case only when the timings fixed for operating his permit are sought to be varied but not otherwise."

2. For answering the issues, which have arisen by reference order it is necessary to note the facts giving rise to W.A.No.412 of 2011. W.A.No.412 of 2011 is being treated as leading case and noticing the facts of the above writ appeal shall be sufficient for deciding all the Writ Appeals.

3. W.A.No.412 of 2011 has been field against the judgment dated 3.3.2011 passed in W.P(C).No.5586 of 2011. The first respondent Mr.M.R.Joy was the writ petitioner. The writ petitioner was granted regular permit vide proceeding dated 20.12.2010 of the Regional Transport Authority, Ernakulam. The decision, however, was subject to settlement of timing. The respondents took the stand that Exhibit P3 permit granted to the writ petitioner can be endorsed only after convening a timing conference and only after settling the timing. The Writ Petition was filed seeking a direction to issue regular permit with Exhibit P2 timings proposed by the writ petitioner reserving the right of the respondent to settle/revise the timings after issue of permit. The Writ Petition was disposed of by the learned Single Judge directing the respondent to issue permit in implementation of Exhibit P3 order with a set of provisional timings. The learned Single Judge has further observed that if, after the permit is issued and the writ petitioner commences service, any other person objects to the timings fixed, it will be open to the respondent to convene a timing conference and settle the timings with notice to the petitioner and other operators. Against the aforesaid judgment, Writ Appeal has been filed by the appellants, who are the existing operators. The appellants' case is that they have preferred their objection for settlement of proposed timings before issue of permit to the first respondent. Hence, feeling aggrieved by the judgment of the learned Single Judge, they filed the appeal with the leave of the Court. When the appeal was being heard by the Division Bench, the Division Bench noticed the Full Bench judgment in Binu Chacko's case (supra) and made observation that certain observations made by the Full Bench that existing operator can raise objection regarding settlement of timings are inconsistent with the other principle laid down by the Full Bench that existing operator has no right to object to the grant of new permits. The Division Bench made a reference to Full Bench, which, in turn, has referred the matter vide its order dated 16.10.2014 for consideration by a Larger Bench.

4. What is the ratio of Full Bench judgment? Whether the Full Bench has committed any error in laying down the ratio? What is the scope and ambit of

Rule 212 of the Kerala Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989

(hereinafter referred to as 'the Rules, 1989')?

These are some of the issues which have to be answered by this Larger Bench.

5. It is useful to quote the relevant statutory provisions, which are necessary for answering the reference made before the Larger Bench.

Chapter V of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988

(hereinafter referred to as 'the Act, 1988') contains the heading 'control of transport vehicles'. Section 70 deals with application for stage carriage permit and Section 71 deals with procedure of Regional Transport Authority in considering application for stage carriage permit. Section 72 refers to grant of stage carriage permit. Right of appeal has been provided for in Section 89 of the Act, which enumerates various contingencies under which a person has the right of appeal. Section 90 provides for revisional power to the State Transport Appellate Tribunal. Section 90 of the Act, 1988 is as follows:

The State Transport Appellate Tribunal may, on an application made to ti, call for the record of any case in which an order has been made by a State Transport Authority or Regional Transport authority against which no appeal lies, and if it appears to the State Transport Appellate Tribunal that the order made by the State Transport Authority or Regional Transport Authority is improper or illegal, the State Transport Appellate Tribunal may pass such order in relation to the case as it deems fit and every such order shall be final:

Provided that the State Transport appellate Tribunal shall not entertain any application from a person aggrieved by an order of a State Transport Authority or Regional Transport Authority, unless the application is made within thirty days from date of the order:

Provided further that the State Transport Appellate Tribunal may entertain the application after the expiry of the said period of thirty days, if it is satisfied that the applicant was prevented by good and sufficient cause from making the application in time: Provided also that the State Transport appellate Tribunal shall not pass an order under this section prejudicial to any person without giving him a reasonable opportunity of being heard."

6. Rule 212 of the Rules, 1989, which has also been referred to is as follows:

(1) The State or Regional Transport Authority may from time to time-

(a) by a general order prescribe a schedule of timings for stage carriages other than those belonging to State Transport Undertakings running on specified routes, or

(b) by a special order prescribe a schedule of timings for each stage carriage other than that belonging to state Transport Undertaking.

(2) The changes ordered by the Transport Authority in the timings of a service shall not be considered as variation of permit under sub- section (3) of section 80 of the Act.

(3) The State Transport Authority or the Regional Transport Authority may, by resolution, delegate to its Secretary the powers conferred on it under this rule subject to any conditions that it may prescribe:

Provided that the State or Regional Transport Authority shall not however vary the timings of a service without giving to the interested permit holders an opportunity to represent their case."

(1) A Regional Transport Authority shall, in considering an application for a stage carriage permit, have regard to the following matters, namely:-

(a) the interest of the public generally;

(b) the advantages to the public of the service to be provided, including the saving of time likely to be effected thereby and any convenience arising from journeys not being broken;

(c) the adequacy of other passenger transport services operating or likely to operate in the near future, whether by road or other means, between the places to be served;

(d) the benefit to any particular locality or localities likely to be afforded by the service;

(e) the operation by the applicant of other transport services, including those in respect of which applications from him for permits are pending;

(f) the condition of the roads included in the proposed route or area; and shall also take into consideration any representations made by persons already providing passenger transport facilities by any means along or near the proposed route or area, or by any association representing persons interested in the provision of road transport facilities recognised in this behalf by the State Government, or by any local authority or police authority within whose jurisdiction any part of the proposed route or area lies:

Provided that other conditions being equal, an application for a stage carriage permit from a co-operative society registered or deemed to have been registered under any enactment in force for the time being and application for a stage carriage permit from a person who has a valid licence for driving transport vehicles shall, as far as may be, be given preference over applications from individual owners."

8. Before the Full Bench in Binu Chacko's case (supra) it was noticed in paragraph 4 that the issue for consideration is whether an existing operator has locus standi to challenge the grant of permit under Section 90 of the Act, 1988. It is useful to quote paragraphs 4 and 9 of the judgment, which is to the following effect:

"4. If the said decision of the Division Bench in C.T.R.B.T. Co-op. Society's case (supra) is to be followed, the writ petitioner has to be non-suited, by holding that he is not entitled to challenge Exhibit P1 grant and thereby does not have the locus to file either a statutory revision under S.90 of the Act, or to file this writ petition. I say so because, the Division Bench in C.T.R.B.T Co-op. Society's case (supra) had categorically found that the existing operators have no right to object to the grant of permit to other stage carriage operators. Thereby it followed an earlier Division Bench decision in Girija Devi v. K.T.Mathew (1991(1) KLT 353).

xx xx xx

9. Learned counsel for the petitioners raised following issues for our consideration:

(1) Whether absence of a statutory right to file objection/representation before the Regional Transport Authority, and absence of a statutory right to be heard in the matter of grant of permit to a rival operator would disentitle an existing operator to invoke the supervisory discretionary jurisdiction of the STAT under S.90 of the Act to impugn an order of the R.T.A granting permit on the ground that the order of the R.T.A is illegal and rendered overlooking relevant provisions of the regulatory statute;

(2) Whether a competitor/rival in trade can be said to be a person aggrieved by an illegal and improper grant of permit/licence to another person in contravention of the provisions of the statute? And

(3) Whether the question of locus standi be considered in the abstract or as a preliminary issue without considering the merits of the contentions touching the legality and propriety of the order, in a given fact situation?"

9. The Full Bench noticed that under the 1939 Act, an existing operator had an opportunity to participate in the decision making process pertaining to the grant of permit. A specific reference was made to Section 47(1) and Section 57(3). The Full Bench noticed that against the above said provision of the old Act, provisions of the new Act have been designed in such a manner that power of authority to refuse permit to the applicant has been substantially curtailed and the right of the rival operator to raise objections against the application for the grant of permit has been taken away. In paragraph 7 of the judgment the following was observed:

"7. As against the above provisions in the old Act, Ss.57, 64, 71, 80 and 90 of the Act have been designed in such a manner that the power of the authority to refuse permit to the applicant has been substantially curtailed. And to effectuate the above purpose the right of the rival operator to raise objections against the application for the grant of permit has been taken away. S.80 of the Act which deals with the procedure for making applications for the grant of permits mandates that the STA/RTA shall not ordinarily refuse to grant an application for permit of any kind made at any time under the Act. S.71 of the act makes it clear that the Legislature wanted to exclude the existing or rival operators from participating in the decision making process. One of the objects of the Act is simplification of procedure and liberalisation in the matter of grant of permits. Sub-clause(1) of S.71 of the act mandates that the R.T.A shall, while considering an application for a stage carriage permit, have regard to the objects of the act. Another important change brought about by the Act is exclusion of a provision similar to the one contained in sub-s.(5) of S.57 of the old Act. The absence of a provision similar to sub- s.(5) of S.57 of the old Act makes the intention of the Legislature clear. A similar intention can be spelt from the absence of provisions similar to those in clause (f) of sub-s.(1) of S.64 of the old Act."

10. The learned Full Bench in Binu Chacko's case (supra) had also referred to and relied on the Division Bench judgment in Girija Devi's case (supra). The Full Bench has taken note and relied on the judgment of the Supreme Court in

Mithilesh Garg v. Union of India (AIR 1992 SC 443)

In the above case the Apex Court has analysed the provisions of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 qua the earlier Act, 1939 and has noticed that there is a marked shift in the policy of grant of permits. In paragraph 6 of the judgment the following has been laid down:

"6. The Parliament in its wisdom has completely effaced the above features. The scheme envisaged under Sections 47 and 57 of the old Act has been completely done away with by the Act. The right of existing operators to file objections and the provision to impose limit on the number of permits have been taken away. There is no similar provision to that of Section 47 and Section 57 under the Act. The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Act shows that the purpose of bringing, in the Act was to liberalise the grant of permits. Section71(1) of the Act provides that while considering an application for a stage carriage permit the Regional Transport Authority shall have regard to the objects of the Act. Section80(2), which is the harbinger of Liberalisation, provides that a Regional 'Transport Authority shall not ordinarily refuse to grant an application for permit of any kind made at any time under the Act. There is no provision under the Act like that of Section 47(3) of the old Act and as such no limit for the grant of permits can be fixed under the Act. There is, however, a provision under Section 71(3) (a) of the Act under which a limit can be fixed for the grant of permits in respect of the routes which are within a town having population of more than five lakhs."

In the above case the Apex Court has approved the liberalised policy of grant of permit and noted that the right of existing permit holders to file objections against an application for grant of permit was taken away.

12. The Apex Court in Mithilesh Garg's case (supra) has noted the salient features of the Act, 1988, especially the liberalised legislative policy of granting permits. As noted above, the right of objection by existing operator as contained in Sections 47 and 57 of the Act, 1939 were completely taken away in the new Act, 1988. Thus, at pre-permit stage, there is no right of objection by an existing operator in the new Act as has already been noticed above. The Writ Petition filed by the existing operator was not entertained by which the petitioner, the existing operator had complained against the liberalised policy for grant of permits under the Act. The contention of the petitioner that their right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India has been affected was also not accepted. The Apex Court had placed reliance on an earlier judgment of the Apex Court reported in

Jasbhai Motibhai Desai v. Roshan Kumar [(1976)1 SCC 671]

It is relevant to note the judgment of the Apex Court in Jasbhai Motibhai Desai's case (supra). In the above case a proprietor of a cinema theatre holding a licence for exhibiting cinematograph films filed the Writ Petition challenging the grant of no objection certificate by the District Magistrate in favour of a rival in the trade. The High Court dismissed the Writ Petition on the ground that no right vested in the appellant had been infringed or prejudiced or adversely affected and as such he was not an aggrieved person to file the Writ Petition. The matter was taken in appeal. In the said context the Apex Court had occasion to consider the meaning of the phrase "aggrieved person". The Apex Court has laid down in paragraph 13 of the judgment that expression "aggrieved person" denotes an elastic and to an extent, an elusive concept, which cannot be confined within the bounds of a rigid, exact and comprehensive definition. The following was laid down in paragraph 13:

"13. This takes us to the further question: Who is an "aggrieved person" and what are the qualifications requisite for such a status? The expression "aggrieved person" denotes an elastic, and to an extent, an elusive concept. It cannot be confined within the bounds of a rigid, exact and comprehensive definition. At best, its features can be described in a broad tentative manner. Its scope and meaning depends on diverse, variable factors such as the content and intent of the statute of which contravention is alleged, the specific circumstances of the case, the nature and extent of the petitioner's interest, and the nature and extent of the prejudice or injury suffered by him. English courts have sometimes put a restricted and sometimes a wide construction on the expression "aggrieved person". However, some general tests have been devised to ascertain whether an applicant is eligible for this category so as to have the necessary locus standi or "standing" to invoke certiorari jurisdiction."

13. The Apex Court noted certain English cases on the context. Few cases pertaining to rival trades were also noticed by the Apex Court. It is useful to quote paragraphs 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 24, which are to the following effect:

"17. The ratio of the decision in Queen v. Justices of Surrey was followed in King v. Groom ex parte. There, the parties were rivals in the liquor trade. The applicants (brewers) had persistently objected to the jurisdiction of the justices to grant the license to one J.K. White in a particular month. It was held that the applicants had a sufficient interest in the matter to enable them to invoke certiorari jurisdiction.

18. A distinguishing feature of this case was that unlike the appellants in the present case who did not, despite public notice, raise any objection before the District Magistrate to the grant of the no-objection certificate, the brewers were persistently raising objections in proceedings before the justices at every stage. The law gave them a right to object and to see that the licensing was done in accordance with law. They were seriously prejudiced in the exercise of that right by the act of usurpation of jurisdiction on the part of the justices.

19. The rule in Grooms case was followed in King v. Richmond Confirming Authority, ex parte Howitt. There also, the applicant for a certiorari was a rival in the liquor trade. It is significant that in coming to the conclusion that the applicant was a "person aggrieved", Earl of Reading, C.J., laid stress on the fact that he had appeared andobjected before the justices and joined issue with them, though unsuccessfully, "in the sense that they said they had jurisdiction when he said they had not".

20. In R. v. Thames Magistrate's Court ex parte Greenbaum, there were two traders in Goulston St., Stepney. One of them was Gritzman who held a license to trade on pitch No. 4 for 5 days in the week and pitch No. 8 for the other two days. The other was Greenbaum, who held a licence to sell on pitch No. 8 for two days of the week and pitch No. 10 for the other days of the week. A much better pitch, pitch No. 2, in Goulston St. became vacant. Thereupon, both Gritzman and Greenbaum applied for the grant of a licence, each wanted to give up his own existing licence and get a new licence for pitch No. 2. The Borough Council considered and decided in favour of Greenbaum and refused Gritzman who was left with his pitches Nos. 4 and 8.

21. Gritzman appealed to the Magistrate. He could not appeal against the grant of a licence to Greenbaum, but only against the refusal to grant a licence to himself. Before the Magistrate, the Borough Council opposed him. The Magistrate held that the Council were wrong to refuse the licence of pitch No. 2 to Gritzman. The Council thereupon made out a licence for Gritzman for pitch No. 2 and wrote to Greenbaum saying that his licence had been wrongly issued. Greenbaum made an application for certiorari to court. The court held that the Magistrate had no jurisdiction to hear the appeal. An objection was taken that Greenbaum had no locus standi. Rejecting the contention, Lord Denning observed:

"I should have thought that in this case Greenbaum was certainly a person aggrieved, and not a stranger. He was affected by the Magistrate's orders because the Magistrate ordered another person to be put on his pitch. It is a proper case for the intervention of the court by means of certiorari."

xx xx xx

24. In Regina v. Liverpool Corporation ex parte Liverpool Taxi Fleet Operators' Association the City Council in exercise of its powers under the town Police Clauses Act, 1847, limited the number of licensesto be issued for hackney carriages to 300. The Council gave an undertaking to the associations representing the 300 existing licence holders not to increase the number of such license holders above 300 for a certain period. The Council, disregarding this undertaking, resolved to increase the number. An association representing the existing license holders moved the Queens' Bench for leave to apply for orders of prohibition, mandamus and certiorari. The Division Bench refused. In the Court of Appeal, allowing the association's appeal, Lord Denning, M.R. observed at pp. 308, 309:

"The taxicab owners' association come to this Court for relief and I think we should give it to them. The writs of prohibition and certiorari lie on behalf of any person who is a `person aggrieved' and that includes any person whose interests may be prejudicially affected by what is taking place. It does not include a mere busybody who is interfering in things which do not concern him; but it includes any person who has a genuine grievance because something has been done or may be done which affects him: See Attorney General of the Gambia v. N'Jie and Maurice v. London County Council. The taxicab owners' association here have certainly a locus standi to apply for relief."

14. Extending the concept of locus standi to apply to a writ of certiorari, the following was laid down in paragraphs 37, 38 and 39 of the judgment:

"37. It will be seen that in the context of locus standi to apply for a writ of certiorari, an applicant may ordinarily fall in any of these categories: (i) "person aggrieved"; (ii) "stranger"; (iii) busybody or meddlesome interloper. Persons in the last category are easily distinguishable from those coming under the first two categories. Such persons interfere in things which do not concern them. They masquerade as crusaders for justice. They pretend to act in the name of pro bono publico, though they have no interest of the public or even of their own to protect. They indulge in the pastime of meddling with the judicial process either by force of habit or from improper motives. Often, they are actuated by a desire to win notoriety or cheap popularity; while the ulterior intent of some applicants in this category, may be no more than spoking the wheels of administration. The High Court should do well to reject the applications of such busybodies at the threshold.

38. The distinction between the first and second categories of applicants, though real, is not always well-demarcated. The first category has, as it were, two concentric zones; a solid central zone of certainty, and a grey outer circle of lessening certainty in a sliding centrifugal scale, with an outermost nebulous fringe of uncertainty. Applicants falling within the central zone are those whose legal rights have been infringed. Such applicants undoubtedly stand in the category of "persons aggrieved". In the grey outer circle the bounds which separate the first category from the second, intermix, interfuse and overlap increasingly in a centrifugal direction. All persons in this outer zone may not be "persons aggrieved".

39. To distinguish such applicants from "strangers", among them, some broad tests may be deduced from the conspectus made above. These tests are not absolute and ultimate. Their efficacy varies according to the circumstances of the case, including the statutory context in which the matter falls to be considered. These are: Whether the applicant is a person whose legal right has been infringed? Has he suffered a legal wrong or injury, in the sense, that his interest, recognised by law, has been prejudicially and directly affected by the act or omission of the authority, complained of? Is he a person who has suffered a legal grievance, a person "against whom a decision has been pronounced which has wrongfully deprived him of something or wrongfully refused him something, or wrongfully affected his title to something?" Has he a special and substantial grievance of his own beyond some grievance or inconvenience suffered by him in common with the rest of the public? Was he entitled to object and be heard by the authority before it took the impugned action? If so, was he prejudicially affected in the exercise of that right by the act of usurpation of jurisdiction on the part of the authority? Is the statute, in the context of which the scope of the words "person aggrieved" is being considered, a social welfare measure designed to lay down ethical or professional standards of conduct for the community? Or is it a statute dealing with private rights of particular individuals?"

15. Noticing the facts of the above case the Apex Court noted that in substance the stand of the appellant was that setting up of rival cinema theatre in the town will adversely affect his commercial interest. The Apex Court in the context has laid down that such injury cannot be held to be legal injury or legally protected interest, hence, there shall be no locus standi. The following was laid down in paragraphs 47 and 48 of the judgment:

"47. Thus, in substance, the appellant's stand is that the setting up of a rival cinema house in the town will adversely affect his monopolistic commercial interest, causing pecuniary harm and loss of business from competition. Such harm or loss is not wrongful in the eye of law, because it does not result in injury to a legal right or a legally protected interest, the business competition causing it being a lawful activity. Juridically, harm of this description is called damnum sine injuria, the term injuria being here used in its true sense of an act contrary to law. The reason why the law suffers a person knowingly to inflict harm of this description on another, without holding him accountable for it, is that such harm done to an individual is a gain to society at large.

48. In the light of the above discussion, it is demonstrably clear that the appellant has not been denied or deprived of a legal right. He has not sustained injury to any legally protected interest. In fact, the impugned order does not operate as a decision against him, much less does it wrongfully affect his title to something. He has not been subjected to a legal wrong. He has suffered no legal grievance. He has no legal peg for a justiciable claim to hang on. Therefore he is not a "person aggrieved" and has no locus standi to challenge the grant of the no-objection certificate."

16. The Apex Court in the context of the above case where he was challenging setting up of a rival cinema theatre has held that there was no injury or legally protected interest and mere adverse effect on commercial interest or loss of business from competition are not sufficient to cloth him with the locus standi to file the Writ Petition. The Full Bench in Binu Chakco's case (supra) has rightly relied on the said ratio of the Apex Court judgment in Jasbhai Motibhai Desai's case (supra). The Full Bench in Binu Chacko's case (supra) has relied on and approved two earlier Division Bench judgments of this Court, i.e., Girija Devi v. K.T.Mathew (1991(1) KLT 353) and

T.R.B.T. Co-op. Society Ltd. v. Mathew Job (1992(1) KLT 297)

In Girija Devi's case (supra) the Regional Transport Authority has granted a stage carriage permit to the appellant for a slightly different route. The appellant had challenged the decision of the Regional Transport Authority before the State Transport Appellate Tribunal. The Tribunal set aside the order of the Regioinal Transport Authority and granted the permit in respect of the route as prayed for by the appellant. The existing operator challenged the order of the Tribunal in O.P.No.8127 of 1990. The learned Single Judge allowed the Writ Petition quashing the order of the Tribunal and remitted the case to the State Transport Appellate Tribunal. Against the judgment of the Single Judge, Writ Appeal was filed and the Division Bench held that existing permit holder can raise the only grievance about the timings and that has to be taken care of by the Secretary, Regional Transport Authority.

17. The Division Bench judgment in T.R.B.T. Co-op. Society Ltd.'s case (supra) had held that existing operators have no right to object to the grant of permit to other stage carriage operators. The Full Bench in Binu Chacko's case (supra) has rightly laid down that existing operator cannot invoke the revisional jurisdiction on the sole ground that the grant of permit to the opposite party prejudicially affects his right. The enunciation of the said ratio is fully in accordance with the law laid down by the Apex Court in Jasbhai Motibhai Desai's case (supra). However, in paragraph 28 the Full Bench has also observed that existing operator can challenge only those orders against which he can have a legal grievance. It is useful to quote paragraph 28 of the Full Bench judgment, which contains the ratio of the Full Bench, which is to the following effect:

"28. We are of the view that the existing operator cannot invoke the revisional jurisdiction on the sole ground that the grant of permit to the opposite party prejudicially affects his rights. It is not as though he can impeach each and every order of the RTA or STA alleging illegality or impropriety. He can challenge only those orders against which he can have a legal grievance. He cannot be a person aggrieved in respect of every action or decision of RTA or STA. There are grievances which would give rise to a cause of action exclusively for the passengers only or sometimes to a local authority and the like if the existing operator is given the right to challenge the very grant of permit or renewal of permit on the ground that he is aggrieved by such grant, it will amount to resurrecting a right which he was entitled to avail only under the old Act. It will be illogical and irrational to interpret the expression "person aggrieved" in S.90 of the Act in such a manner as to take away the right given to a new entrant at the pre-permit stage to have a permit under the act without obstruction from those already in the business, the very moment he is granted or issued a permit. Under normal circumstances, grievance of the existing operator shall be confined to disputes relating to settlement of timings and cannot be entertained against the grant of permit or renewal of permit as such. We are unable to concur with the reasoning and the final conclusion arrived at by the learned Judges in D.L.Sadashiva Reddy v. P.Lala Sheriff (AIR 1999 Karnataka 5). We agree with the views expressed by the Division Bench in Girija Devi v. K.T.Mathew (1991(1) KLT 353) and in C.T.R.B.T. Cop-op. Society's case that an existing operator will be a person aggrieved as far as settlement of timings is concerned. However, it may not be proper or expedient to restrict the scope of the words "person aggrieved" to settlement of timings only, though under the scheme of the act, existing operators may have in the normal course, legal grievance against settlement of timings only. We, therefore, do not rule out any other grievance of a similar nature which would tilt the balance in favour of one operator and against another as a consequence of orders issued by R.T.A or S.T.A. The applicant is required not only to establish that the order impugned suffers from illegality or impropriety of a substantial nature but also has to discharge the burden to satisfy the tribunal that he has a legal grievance against that order, and therefore, is a person aggrieved. This exercise the STAT has to do by applying its mind to the facts and circumstances of each case and this implies that the tribunal may not throw a revision petition overboard at the threshold."

The Full Bench has further held that under normal circumstances, the grievance of the existing operator shall be confined to disputes relating to settlement of timings and cannot be entertained against the grant of permit or renewal of permit as such.

18. Rule 212 of the Rules, 1989, which has already been extracted above, indicates that existing operators have a statutory right to be heard before varying the timings of their services. The State or Regional Transport Authority is obliged to give opportunity to permit holders to represent their case in the event the timings of services are to be varied. Whether the existing operator has only a statutory right as contained in sub-rule (3) of Rule 212 or there is any other statutory right or there can be any other circumstances in which existing permit holder can be held to be a person aggrieved for challenging a grant of permit by filing revision under Section 90 of the Act, 1988 or by filing a Writ Petition under Article 226 of the Constitution or even filing a Writ Appeal, are the questions which are to be further examined by us.

19. The Act, 1988 contains a statutory provision for grant of a stage carriage permit. Section 71 of the Act, 1988 deals with procedure of Regional Transport Authority in considering application for stage carriage permit. Section 71(3) empowers the State Government to limit the number of stage carriages generally or of any specified type, as may be fixed and specified in the notification, operating on city routes in towns with a population of not less than five lakhs. Section 71(3)(a) is quoted as under:

"71. Procedure of Regional Transport Authority in considering application for stage carriage permit.-

xx xx xx

(3)(a) The State Government shall, if so directed by the Central Government having regard to the number of vehicles, road conditions and other relevant matters, by notification in the Official Gazette, direct a State Transport Authority and a Regional Transport Authority to limit the number of stage carriages generally or of any specified type, as may be fixed and specified in the notification, operating on city routes in towns with a population of not less than five lakhks."

Section 80(2) of the Act, 1988 provides that Regional Transport Authority or State Transport Authority shall not ordinarily refuse to grant an application for permit. Sub- section (2) of Section 80 of the Act, 1988, however, contains a proviso, which is to the following effect: "80.Procedure in applying for and granting permits.-

(1) xx xx xx

(2) A Regional Transport Authority, State Transport Authority or any prescribed authority referred to in sub-section (1) of section 66 shall not ordinarily refuse to grant an application for permit of any kind made at any time under this Act: Provided that the Regional Transport Authority, State Transport Authority or any prescribed authiority referred to in sub-section (1) of section 66 may summarily refuse the application if the grant of any permit in accordance with the application would have the effect of increasing the number of stage carriages as fixed and specified in a notification in the Official Gazette under clause (a) of sub-section (3) of section 71 or of contract carriages as fixed and speecified in a notification in the Official Gazette under clause (a) of siub-section (3) of section 74: Provided further that where a Regional Transport Authority, Stage Transport Authority or any prescribed authority referred to in sub-section (1) of Section 66 refuses an application for the grant of a permit of any kind under this Act, it shall give to the applicant in writing its reasons for the refusal of the same and an opportunity of being heard in the matter."

20. The above provision clearly indicates that there may be circumstances when number of stage carriage permits are limited and in the event stage carriage permit is granted, violating the said statutory prohibition where still the existing permit holder shall have no right to file revision under Section 90.

21. According to us, in a situation where permit granted is clearly in teeth of the statutory provision, the existing permit holders cannot be denied their right to file application under Section 90. The power of revision has been entrusted on the Tribunal to ensure that the State or Regional Transport Authority does not pass an illegal or improper order. In an event an illegal order is passed by the State or Regional Transport Authority and there being a power of the State Transport Appellate Tribunal to correct the said order, denial of right to file a revision of existing permit holder shall not advance the object of the Act. It is relevant to notice that the power which was contained in the 1939 Act by section 64A, there was power to exercise the revisional jurisdiction "either on its own motion or on an application made to it". In Section 90, there is no suo motu power to exercise revisional jurisdiction. An application for revision under Section 90 is, thus, a must for exercising the revisional jurisdiction. In the event an illegal order is passed and the right of revision is denied to existing permit holders, the wrong shall go uncorrected, which can never be the intention of the legislature. It is useful to notice the observations made by the Apex Court in Mithilesh Garg's case (supra), where the Apex Court has held that the statutory authorities under the Act are bound to keep a watch on the erroneous or illegal exercise of power in granting permit under the liberalised policy. It is useful to quote the following in paragraph 15 of the judgment:

".....The statutory authorities under the Act are bound to keep a watch on the erroneous and illegal exercise of power in granting permits under the liberalised policy."

There may be several other circumstances, where permit is granted in a clear statutory violation. In those events also, it is to be held that right of revision cannot be denied to existing permit holders. It is relevant to note that the Apex Court in

M.S.Jayaraj v. Commissioner of Excise, Kerala and others [(2000)7 SCC 552]

had occasion to consider a similar argument regarding locus standi of a rival businessman, who had challenged an order of Excise Commissioner siting a liquor shop. The Division Bench of the High Court quashed the order of the Excise Commissioner, against which a Special Leave Petition was filed. One of the grounds taken in the Special Leave Petition was that the High Court ought not to have entertained the Writ Petition filed by the respondent, who was the rival businessman, who has no locus standi to file the Writ Petition. In the Writ Petition it was contended that Excise Commissioner had no jurisdiction to permit a liquor shop owner to move out of the range and there was violation of law. The Apex Court noticed the earlier judgment of the Apex Court in Jasbhai Motibhai Desai's case (supra) and laid down the following in paragraphs 12 and 14 of the judgment:

"12. In this context we noticed that this Court has changed from the earlier strict interpretation regarding locus standi as adopted in Nagar Rice & Flour Mills v. N. Teekappa Gowda & Bros. and Jasbhai Motibhai Desai v. Roshan Kumar and a much wider canvass has been adopted in later years regarding a person's entitlement to move the High Court involving writ jurisdiction. A four-Judge Bench in Jasbhai Motibhai Desai pointed out three categories of persons vis-`-vis the locus standi:

(1) a person aggrieved;

(2) a stranger; and

(3) a busybody or a meddlesome interloper.

Learned Judges in that decision pointed out that anyone belonging to the third category is easily distinguishable and such person interferes in things which do not concern him as he masquerades to be a crusader of justice. The judgment has cautioned that the High Court should do well to reject the petitions of such busybody at the threshold itself. Then their Lordships observed the following: (SCC p. 683, para 38)

"38. The distinction between the first and second categories of applicants, though real, is not always well demarcated. The first category has, as it were, two concentric zones; a solid central zone of certainty, and a grey outer circle of lessening certainty in a sliding centrifugal scale, with an outermost nebulous fringe of uncertainty. Applicants falling within the central zone are those whose legal rights have been infringed. Such applicants undoubtedly stand in the category of `persons aggrieved'. In the grey outer circle the bounds which separate the first category from the second, intermix, interfuse and overlap increasingly in a centrifugal direction. All persons in this outer zone may not be `persons aggrieved'."

xx xx xx

14. In the light of the expanded concept of the locus standi and also in view of the finding of the Division Bench of the High Court that the order of the Excise Commissioner was passed in violation of law, we do not wish to nip the motion out solely on the ground of locus standi. If the Excise Commissioner has no authority to permit a liquor shop owner to move out of the range (for which auction was held) and have his business in another range it would be improper to allow such an order to remain alive and operative on the sole ground that the person who filed the writ petition has strictly no locus standi. So we proceed to consider the contentions on merits."

22. The Apex Court took the view that in the light of the extending concept of locus standi and the fact that order of the Excise Commissioner was passed in violation of law, the Writ Petition could not have been thrown on the ground of locus standi. In another judgment in

Sai Chalchitra v. Commissioner, Meerut Mandal and others [(2005)3 SCC 683]

locus standi of a cinema licensee to challenge grant of licence, which was in violation of provisions of the U.P. Cinemas (Regulation) Act, 1955 was upheld. The Apex Court has upheld the locus standi of the writ petitioner. Paragraphs 2 to 5 of the above judgment are relevant, which are quoted as below:

"2. The main grievance of the appellant before the High Court was that Prakash Palance Video Parlour, Respondent 3 was situated within 350 metres from Sai Chalchitra and hence no licence could be granted to Respondent 3 to run a video parlour under the U.P. Cinema (Regulation of Exhibition by Means of Video) Rules, 1988. It was also asserted that the exhibition of video films by Respondent 3 had badly affected the cinema business of the appellant as the video parlour was situated very close to the cinema hall of the appellant. It was also submitted that the grant of licence in favour of Respondent 3 was in violation of the provisions contained in Sections 7(1-A)(a), (b) and (c) of the U.P. Regulation of Cinema Act, 1955. Under Section 7(1-A), licence could be cancelled or revoked on the following grounds:

"(a) that the licence was obtained through fraud or misrepresentation; or

(b) that the licensing authority or the State Government while considering the application or appeal, as the case may be, under Section 5 was under a mistake as to a matter essential to the question of grant or refusal of licence; or

(c) that the licensee has been guilty of breach of the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder or of any conditions or restrictions contained in the licence, or of any direction issued under sub-section (4) of Section 5; or"

3. The writ petition was contested by the State of U.P. as well as Respondent 3.

4. Learned Single Judge, before whom the writ petition came up for hearing, dismissed the writ petition on the locus standi of the appellant to file the writ petition without going into the other questions of law. It was observed that the appellant could not raise a grievance against his rival in the trade particularly when the rival in trade, as in the instant case, was exhibiting cinematograph films much before the appellant was granted the licence. It was held that the appellant had not been denied or deprived of its legal right to exhibit the films and, therefore, he had not sustained any legally protected interest. It was also observed that the order of the Commissioner did not operate as a decision against the appellant as the appellant had not suffered any legal wrong. The writ petition filed by the appellant was held not to be maintainable.

5. After hearing the counsel for the parties, we are of the opinion that the High Court clearly erred in dismissing the writ petition filed by the appellant on the ground of locus standi. The appellant being in the same trade as Respondent 3 has a right to seek the cancellation of the licence granted to Respondent 3 being in violation of the Act and the Rules."

23. We, thus, conclude that although the existing permit holders have no right and cannot be held to be aggrieved person when they sought to challenge a grant of permit on the sole ground, that grant of permit shall prejudicially affect their commercial interest. But, in case where the grant is in a statutory violation, the right to file revision under Section 90 or file Writ Petition or Writ Appeal cannot be denied.

24. Now we come to Rule 212 of the Kerala Motor Vehicles Rules on which much emphasis has been made. Sri.C.S.Manilal, learned Special Government Pleader appearing for the State who has emphatically submitted that the existing permit holder has only right to object regarding timings. He submits that under the proviso to Rule 212(3), there is obligation on the State or Regional Transport Authority not to vary the timings of a service without giving to the interested permit holders an opportunity to represent their case. He submits that the right of the existing permit holder is only to object to the timing of the permit. Rule 212 contains the heading "schedule of timings". Rule 212 was a Rule framed regulating the schedule of timing. Rule 212 empowers the State Transport Authority by a special order to prescribe a schedule of timings for each stage carriage other than that belonging to State Transport Undertaking and may also vary the timings of a service with the condition that the said variance can be made only after giving opportunity to interested permit holders. The said Rule has been designated only for a particular purpose, i.e., with regard to timing. The said Rule cannot be treated to be repository of rights of existing permit holder, nor can be a condition with regard to their right to file application under Section 90 of the Act, 1988. Rule 212 shall not control or regulate interpretation of Section 90. Section 90 has been set out for a different purpose and object and Rule 212 has been set out for the purpose of carrying out the purposes of the Act and regulating the timings only. The submission of learned Government Pleader that the only contingency in which right of filing of application under Section 90 can be considered to existing permit holder is regarding timing, thus, does not appeal to us. Section 90 has to be given a wide interpretation and cannot be confined to limited right which was given to existing permit holders under Rule 212.

25. Now we come back to paragraph 28 of the Full Bench decision in Binu Chacko's case (supra). The Full Bench while laying down the ratio, has used the words

"under normal circumstances, grievance of the existing operator shall be confined to disputes relating to settlement of timings and cannot be entertained against the grant of permit or renewal of permit as such".

The said ratio itself explains that there may be cases where the existing permit holders may have right to move an application for revision even though their applications may not be confined to the timings of the permit alone. In the very said paragraph the following has also been observed that

"we, therefore, do not rule out any other grievance of a similar nature which would tilt the balance in favour of one operator and against another as a consequence of orders issued by R.T.A or S.T.A. ...".

The above observation of the Full Bench make itself clear that the Full Bench was also conscious that there may be grievances of various nature, which may be raised and which may relate to illegality or impropriety of substantial nature. The Full Bench further opined in the said case that the person has to discharge the burden to satisfy the Tribunal that he has a legal grievance against that order, so as to make him a person aggrieved.

26. In view of the foregoing discussion, we are of the opinion that Section 90 cannot be interpreted in a manner to exclude or prohibit an application for revision at the instance of existing permit holder in all circumstances. We further hasten to add that whether a person, who is filing application can be said to be "a person aggrieved" is a question which has to be decided in the facts of each case. There may be cases where the permit holder cannot be said to be aggrieved, nor he can be said to have any right to move the application. But, then the cases under which the permit holder can file application or cannot file an application, cannot be enumerated, nor it is necessary for us to enumerate circumstances under which application can be filed or application cannot be filed. It depends on the facts of each case, which has to be examined at the wisdom of the Appellate Tribunal and we leave the matter there.

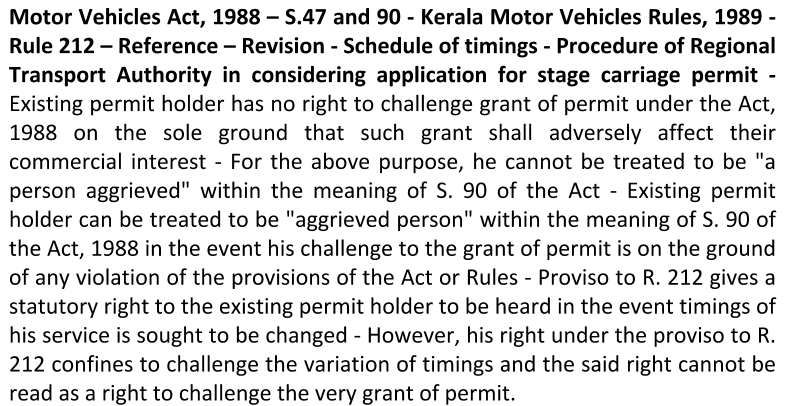

27. In view of the foregoing discussions, we answer the reference in the following manner:

(1) The existing permit holder has no right to challenge grant of permit under the Act, 1988 on the sole ground that such grant shall adversely affect their commercial interest. For the above purpose, he cannot be treated to be "a person aggrieved" within the meaning of Section 90 of the Act, 1988.

(2) The existing permit holder can be treated to be "aggrieved person" within the meaning of Section 90 of the Act, 1988 in the event his challenge to the grant of permit is on the ground of any violation of the provisions of the Act or Rules.

(3) The proviso to Rule 212 gives a statutory right to the existing permit holder to be heard in the event timings of his service is sought to be changed. However, his right under the proviso to Rule 212 confines to challenge the variation of timings and the said right cannot be read as a right to challenge the very grant of permit.

(4). The Full Bench judgment in Binu Chacko's case (supra) is explained and clarified in the above manner.

28. We now proceed to decide all the Writ Appeals, which are listed before us.

W.A.No. 576 of 2011

29. A memo has been filed by learned counsel for the appellant that the appeal be dismissed as not pressed. The Writ Appeal is dismissed as not pressed.

W.A.Nos.385 of 2011

30. This Writ Appeal has been filed by a third party, who was not a party to the Writ Petition. This Court has granted leave to file the Writ Appeal. The Writ Petition was filed by the first respondent herein praying for the following reliefs:

(i) Issue a writ in the nature of mandamus commanding the 2nd respondent to forthwith issue the regular permit granted under Exhibit P3 order of the Regional Transport Authority, Thrissur with Exhibit P2 timings proposed by the petitoiner, reserving the right of the respondent to settle/revise the timings after the issue of the permit, on receipt of genuine objections.

(ii) Issue such other appropriate writ, order or direction as this Hon'ble Court may deem fit and proper in the facts and circumstances of the case."

31. The writ petitioner was already issued regular permit by Exhibit P3 order with Exhibit P2 timings proposed by the petitioner. But, the timings were to be settled/revised by the authorities.

32. The learned Single Judge, by the impugned judgment dated 11th February, 2011, has disposed of the Writ Petition with the following directions:

"The respondent shall within one week from the date on which the petitioner produces a copy of this judgment before him, issue a set of timings to the petitioner on a provisional basis and shall immediately thereafter issue the permit to the petitioner. The respondent shall thereafter invite objections from other stage carriage operators and settle the timings within a period of three months thereafter. If any existing stage carriage operator is aggrieved by the time schedule issued to the petitioner pursuant to the directions in this judgment, it will be open to him or her to object to the timings and to request the respondent to convene a timing conference to settle the timings expeditiously."

33. The third party, who is the existing permit holder, has come up in this Writ Appeal challenging the aforesaid judgment.

34. In view of our answer to the reference as above, existing permit holder can object variance of timing only in accordance with proviso to sub-Rule (3) of Rule 212. It is the mandatory duty of the Regional Transport Authority to give an opportunity, if timings of any existing permit holder is sought to be varied. We have no reason to doubt that the direction issued by the learned Single Judge dated 11.4.2011 has to be complied with by the authority with due regard to Rule 212.

35. In view of aforesaid facts, we see no reason to interfere with the judgment of the learned Single Judge. The Writ appeal is dismissed with the observation that in carrying out the judgment of the learned Single Judge, if not already carried out, appropriate proceedings shall be taken in accordance with Rule 212.

W.A.No.412 of 2011

36. This Writ Appeal has also been filed against the judgment dated 3.3.2011 in W.P(C).No.5586 of 2011 by a third party, who was not a party to the Writ Petition. This Court has already granted permission to file the Writ Appeal. The Writ Petition was filed by the respondent, who was already granted regular permit, but timing as proposed by the petitioner was not being settled, hence the Writ Petition was filed seeking the following reliefs:

"Issue a writ of mandamus commanding the 2nd respondent to forthwith issue the regular permit granted under Exhibit P3 order of the Regional Transport Authority, Ernakulam with Exhibit P2 timings proposed by the petitioner, reserving the right of the respondent to settle/revise the things after the issue of the permit, on receipt of genuine objections."

37. The learned Single Judge by judgment dated 3.3.2011 disposed of the Writ Petition with the following direction:

"I accordingly dispose of the writ petition with a direction to the respondent to issue the permit in implementation of Ext.P3 order with a set of provisional timings. Needful in the matter shall be done expeditiously and in any event within one week from the date on which the petitioner produces a certified copy of the judgment before the respondent. If, after the permit is issued and the petitioner commences service, any other person(s) objects to the timings presently fixed, it will be open to the respondent to convene a timing conference and settle the timings with notice to the petitioner and the other operators operating on the route or sectors thereof. In that event, the time schedule shall be settled expeditiously and in any event within two months from the date on which any objection is received from the existing operators to the time schedule presently fixed."

38. In view of our observation as made above, while answering the reference, we have observed that the existing permit holders are to be heard only when the timings is sought to be varied as contemplated by Rule 212(3). The learned Single Judge has already directed for settling the time schedule expeditiously, after receiving objection from the existing operators. The said direction is fully in consonance with Rule 212 and we see no reason to interfere with the direction.

The reference is answered and all the Writ Appeals are dismissed as above.

ASHOK BHUSHAN ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE

A.M.SHAFFIQUE JUDGE

A.V.RAMAKRISHNA PILLAI JUDGE

A.HARIPRASAD JUDGE

A.K.JAYASANKARAN NAMBIAR JUDGE

vgs12/12/14